O’Leary, B. and McGarry, J. (1996) ‘Exercising Control: the second Protestant Ascendancy, 1920-62’

O’Leary, B. and McGarry, J. (1996) ‘Exercising Control: the second Protestant Ascendancy, 1920-62’, in B. O’Leary and J. McGarry, eds., The Politics of Antagonism: Understanding Northern Ireland, 2. ed., London, Athlone Press, 107-52.

- Northern Ireland (‘NI’) is “the paradigm of state- and nation-building failure in western Europe” (107), as “the product of differential political power” (108).

- External environment (British imperialism and Irish irredentism) also played a key role.

- Three models of an acceptable modern state and citizenship:

- Statist: “people” are all resident adults: multicultural nation-state;

- Nationalist: all members of the nation make up the ‘people’: nation-state;

- Universalist: the entire human species is ‘the people’: global-state.

- Particularist: Only members of an ethnic group are the people: hegemonic state.

- NI between 1920 and 1972 was particularist at the sub-state level.

- “Control is ‘hegemonic’ if it makes an overtly violent ethnic contest for state power either ‘unthinkable’ or ‘unworkable’” (109); where one ethnic community dominates another by extracting the resources it requires from the subordinated one.

- NI from 1920 to 1969:

- Sovereignty formally contested between Ireland and the UK;

- Not fully integrated into either;

- Institutions lacked by-communal legitimacy;

- It was a semi-state ‘regime’ created by the UK.

- Illustration that democratic rule was compatible with tyranny of the majority: territorial, constitutional, electoral, economic, legal, cultural control were pervasive.

- Territorial control:

- Demarcation of 6 Ulster counties as NI with in-built Protestant majority;

- Gerrymandering of local government jurisdictions by UUP to drastically reduce nationalist local councils;

- Boundary commission’s terms of reference and composition were loaded against nationalists’ interests and contributed to its failure.

- Constitutional control:

- Governed under the UK Government of Ireland Act establishing a devolved parliament modelled on Westminster in Belfast:

- majoritarian government under parliamentary sovereignty unrestrained by a constitution;

- unitary form;

- concentration of executive power in one-party Cabinets;

- fusion of executive and legislative power under Cabinet dominance;

- bicameral legislature with lower house much more powerful.

- From 1920 to 1972, only UUP governments in power, characterised by Cabinet predominance: extremely stable.

- Cohesion of the Unionist bloc was key: no incentives to bargains and make concessions to nationalist minority.

- No real checks and balances: not an authentic pluralist democracy.

- Nationalist minority had little at stake in this regime.

- Legislature modeled on adversarial pattern, but parliament’s real task in NI was simply to express Unionist domination (115).

- Upper House was replica of Lower House in terms of membership: did nothing to protect minority.

- Deviated from Westminster model in 2 respects:

- Subordinate parliament could be declared unconstitutional if it violated section of the act outlawing religious discrimination (but did not extend to political opinion; offered no protection against the Special Powers Act; did not protect cultural and communal rights); and

- Proportional representation electoral system.

- No legal aid before 1965;

- Courts were unwilling to strike down Stormont legislation violating division of powers with Westminster: applied permissive ‘pith and substance’ doctrine;

- Administrative separatism:

- Westminster exercised almost no supervision or control over Stormont: NI has more the status of a ‘dominion’ than a subordinate level of local government;

- Stormont abolished Proportional representation system without Westminster interference.

- Governed under the UK Government of Ireland Act establishing a devolved parliament modelled on Westminster in Belfast:

- Electoral control – hegemonic entrenchment of UUP in government & institutionalization of ethnic divisions:

- Electoral domination of local government;

- Restriction of local franchise;

- Retention of company votes;

- Disenfranchisement of anti-UUP voters (Catholics);

- Abolition of PR (STV) and replacement with FPTP;

- Exclusion of relatively recent immigrants from the Irish Free State;

- Conservation of University constituencies;

- British voting system focusing elections on straight nationalist-unionist contest and disadvantaging smaller parties than could fragment unionist vote (125).

- Coercive control: hegemonic control must be backed by coercive resources:

- Creation of UVF (Ulster Volunteer Force), USC (Ulster Special Constabulary), RUC (Royal Ulster Constabulary) in the 1920s;

- Catholics did not join the police: RUC seen as “Protestants with guns” (126);

- Politically subordinated to the ruling party (UUP).

- Legal control:

- 1922 Civil Authorities (Special Powers) Act (permanent after 1993): draconian piece of legislation (internment without trial; arrest without warrant; curfews; prohibition of inquests; right to compel people to answer questions or be guilty of an offence…);

- 1952 Public Order Act: control non-violent forms of political opposition;

- 1954 Flags and Emblems Act: outlawed symbolic displays of nationalist allegiance.

- Overwhelmingly Protestant judiciary integrated into the UUP.

- Economic Control:

- Direct and indirect discrimination in employment and in public housing;

- Both horizontal, inter-class stratification (upper occupational classes), and horizontal, intra-class stratification (superior positions within occupations within same class), as well as vertical stratification (higher status industries and locations) favoring Protestants.

- Catholics constituted a majority of unemployed;

- UUP positioned at the center of a system of patronage.

- Administrative Control:

- Two key aspects: housing management and public employment.

- Housing segregation maintained predictable electoral outcomes and prevented development of mixed communities.

- Maintained clientelism, with UUP as an effective cross-class party.

- This is evidence of systematically organized domination and control of an ethnic group by another.

- It also shows that the Westminster model of government is compatible with hegemonic control: after 1920, NI was a particularist regime exercising hegemonic control: it seemed to be “a hermetic system which seemed incapable of change or reform” (135)

- Cultural control: Orange order marches –‘representative violence’ leading to ‘communal deterrence’ (140).

- Motivations for hegemonic control (UUP):

- Feared incorporation into a Catholic Irish nation-state (Irish nationalism & irredentism);

- Betrayal by the UK: Britain would abandon NI to the Dublin Parliament if expedient, either totally or through appeasement tactics; Unionists’ strategic dilemma: full integration with UK would make NI Protestants more British but would deprive them of tools of hegemonic control in NI and therefore more vulnerable to abandonment in future Anglo-Irish negotiations;

- Insurrection by Catholic minority: both violent (IRA) and non-violent: requires repressive security against those disloyal, so as to control them effectively: “Thus the colonial legacy was preserved into the liberal democratic era” (140).

- Fragmentation of Protestant community:

- Politics as a zero-sum game: need for strong and resilient unity;

- Fear of betrayal from within very powerful;

- Modernising Unionist elites might move away from the hegemonic control model and sense of group solidarity;

- At least Two Unionist political cultures:

- Ulster loyalist ideology: settler-ideology;

- Ulster British ideology: liberal political values refuting above.

- “The environment in which hegemonic control was maintained shows that the development and sustenance of the fears of Ulster Protestants is comprehensible without recourse to a historicist and essentialist conception of their identity” (141).

- External environment of hegemonic control:

- British state-development:

- Ill-equipped to deal with NI because of its constitutional tradition;

- NI could not be a miniature of the British political system;

- Why was NI not integrated into the British political system after 1920?

- The Anglo-Irish Treaty was regarded as the final settlement of the Irish question, and no one wanted to reopen it;

- Now Irishmen were fighting Irishmen rather than British;

- Stormont Parliament was intended to keep

Irish issues out of British politics, with reduction of Irish MPs at Westminster; - UK party competition in the 1920s and 1930s focuses on economic and class cleavages, whilst religious and territorial problems receded in importance due to the Irish settlement – thus increasing British systemic stability;

- Ambitious British politicians were no longer interested to raise Irish questions at Westminster.

- Labour refused to organize in NI: it was a place best left as a place apart.

- Tories’ ties with UUP meant they also did not want to bring about changes.

- “Hegemonic control, provided its uglier manifestations were not too visible, was preferable for British policy-makers to the known historical costs of direct intervention and management of Irish affairs”

- Integration of NI into the British state would have further soured relations with the Irish state (144).

- 1949 Ireland Act: NI remains part of the UK as long as its Parliament wants it to be. By then, hegemonic control was well entrenched, with a logic of its own (145).

- Irish nation-building failure:

- Mimetic version of British failure;

- Irish cultural nationalism reinforced the inter-Irish divide;

- Irish nationalism mirrored exclusivism and sectarianism of Ulster unionism;

- Development of Irish Free State facilitated consolidation of hegemonic control in NI by UUP;

- Fianna Fail and Fine Gael party competition in Ireland had three mutually reinforcing effects that all reinforced partition by excluding Ulster Protestants from the Irish nation;

- “Irish state-building, logically but unintentionally, took place at the expense of pan-Irish nation-building. The symmetry is evident: British state-maintenance also took place at the expense of pan-British nation-building in Northern Ireland. Hegemonic control was the joint by-product of these nation-building failures.” (147).

- British state-development:

Peleg, I. (2007) ‘Classifying Multinational States’

Peleg, I. (2007) ‘Classifying Multinational States’, in I. Peleg, Democratizing the Hegemonic State, Cambridge, CUP, 78-104.

- How does a hegemonic state (‘HS’) transform into a more inclusive polity?

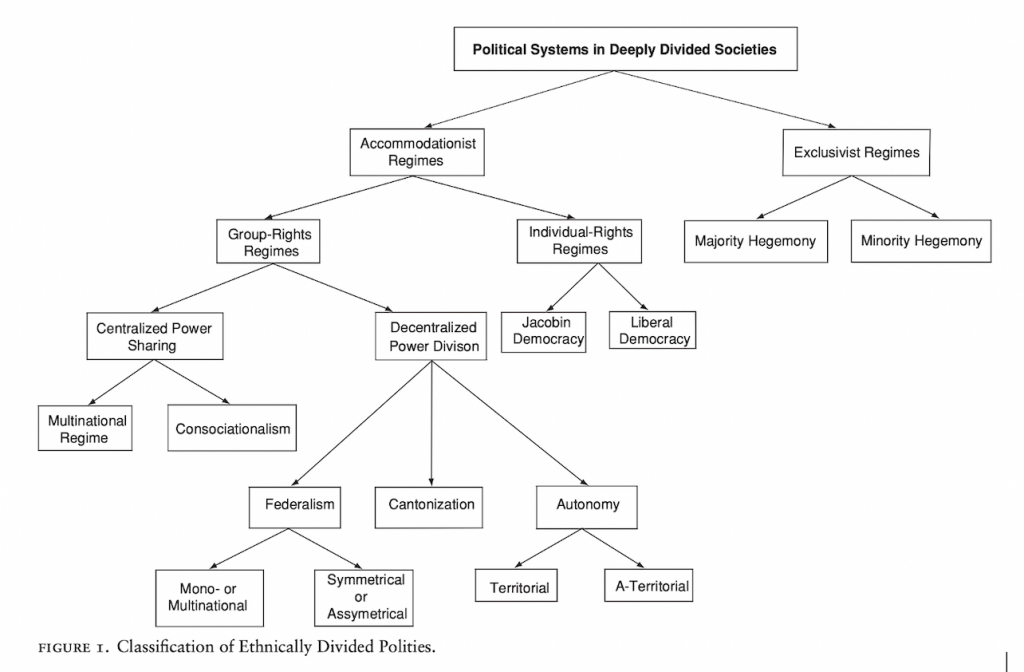

- Classificatory system with both static and dynamic components, that helps studying HSs’ potential for transformation and focuses on five modes of reaction adopted by states in deeply divided societies.

- Classification

- Key issues:

- Units being classified: societies that are deeply divided ethnically – at least two distinct groups (subjective self-identification based on enduring social constructs desired by the group or imposed by others) living within the same political space. Key question: Does the system allow dual identities? Accomodationist states vs. ethnohegemonies.

- Logic of classification: broad – deals with both democratic and non-democratic systems; each type of regime identified is both logically possible and empirically identifiable;

- Importance of classification: concerned primarily with transformation of hegemonic regimes into accommodationist systems;

- Useful classificatory system: analyses politics in deeply divided societies; however, it is oversimplified, accepts that states can adopt a mixture of policies, it is not exhaustive, and regimes can be found in combination.

- Functions of the classificatory system:

- Highlight differences between political regimes in deeply divided societies;

- Describe differences;

- Explain differences;

- Offer some prescriptions regarding possible transformation of hegemonic regimes into more accommodationist ones.

- Three key conditions:

- Empirical

- Broad

- Explicit

- Accomodationist (state-centric: recognizes its own diversity by balancing interests of various ethnic groups) vs. exclusivist (ethno-centric: enhances and perpetuates dominance of one group over the others) multinational state: what conditions allow the transformation of the latter into the former?

- States can pursue a mixture of both approaches at the same time towards various ethnic groups.

- Once accomodationism takes over as a characteristic of the state, its identification with only one ethnic group weakens and it becomes committed to either neutrality or reconciliation.

- Exclusivist regimes institutionalize the dominance of one ethnic group over all others; the ‘nation’ is more central that the state, which is merely an institutional tool of the former, whose form or design may be transformed.

- Two types of hegemonic exclusivist regimes:

- Majority-based: majority rules over a minority (ethnoocracy: Smooha); relatively informal discrimination against minority groups, especially in democracies; semi-consociational arrangements can emerge over time; can even move towards forms of liberal democracy: transformation from exclusivism to accomodationism is difficult (problem of ‘ethnic overbidding’ 88), but possible.

- Minority-based: minority rules over a majority; formal, official, explicit, public discrimination against both minority groups and individuals belonging to them; incompatible with any form of pluralism, based on brute force.

- Democratization breeds opposition to ethnic exclusivity.

- Hegemonic exclusivism can survive in the short- to medium-term, but is likely to be overthrown in the long run because it breeds radical resistance.

- Two types of accommodationist regimes:

- Individuals-rights based: all citizens are equal before the law; state is neutral towards social groups; unfriendly towards any notion of group rights: privatization of ethnicity; attempts to foster an overarching civic identity – clear preference for integration.

- Group-rights based: power-sharing and power-division variants; fully developed liberal democracies can afford recognition of some group rights.

- “[A]lthough individual-based democracy is altogether a very attractive regime, it often does not respond to the needs of all ethnic groups within a deeply divided society” (92).

- Very problematic to move from individual to group rights regimes: difficult to define authoritatively which groups are entitled to what rights.

- Individual and group rights can overlap: ex – affirmative action.

- Two types of individual-based regimes:

- Liberal democracies: favor decentralisation – USA, UK.

- Jacobin democracies: promote cultural centralism – France, Turkey; one dominant state-building ethnic group thinking of itself as ‘the nation’; have adapted over time because assimilationism is increasingly illegitimate:

- Extensive welfare states not unrelated to ethnic stratification;

- Ethnic associations benefit from governmental financial assistance;

- Regional languages experiencing a rebirth in education systems.

- “[I]n deeply divided societies the principles of liberal democracy, based on individual rights, while important and even crucial, are insufficient for creating a stable and just polity” (95): need to be complemented by group rights, based on principle of ‘diversification’.

- Different types of group-rights regimes:

- Centralised power-sharing vs. decentralised power-division regimes: both serve as modes for establishing stable interethnic regimes;

- Within power-sharing regimes (trust and cooperation), difference between consociational and bi- or multinational regimes (higher order of power-sharing; very rare): grand coalitions where elite groups make common decisions based on relatively even distribution of powers;

- Within power-division regimes (agree to avoid each other), three approaches: autonomy (both separate and shared power areas, both Territorial and non-territorial -personal, cultural- autonomy), federalism (mononational and multinational; symmetrical vs. asymmetrical), cantonization (ethnic and territorial power division to minimize ethnic conflict and maximize state cogerence): clear distribution of powers; dominant nation grants limited powers to weaker ethnicities. Hegemonic states can be transformed into accommodationist ones via various types of federalism (ex: asymmetrical), but can also lead to separatism movements and secession attempts (biethnic federations are especially fragile). Emergence of supranational bodies (ex: EU) allows for development of more creative power-sharing schemes in the future (100).

- Some believe that, in deeply divided societies, consociationalism is the only game in town; but it has very mixed track record and clear limits (outbidding: Northern Ireland).

- How do hegemonic regimes transform themselves into either individual-based or group-based accomodationism through dynamic processes of change (direction, intensity, internal/external) ?

- Seven types of potential transformation in multi-national states:

- Status quo;

- Moderate democratization;

- Radical (‘mega-constitutional’) democratization;

- Moderate (‘benign’) ethnicization;

- Radical (‘malignant’) ethnicization;

- Peaceful separation;

- Forced partition.

Smooha, S. (2002) ‘The model of ethnic democracy: Israel as a Jewish and democratic state’

Smooha, S. (2002) ‘The model of ethnic democracy: Israel as a Jewish and democratic state’, Nations and Nationalism 8 (4), 475-503.

- Liberal nation-state in decline in West: shift towards multicultural civic democracy.

- Outside west, other countries are consolidating non-civic form of democracy subservient to a single ethnic nation: ethnic democracy or ‘ethnocracy’. Ex: Israel.

- Two main forms of democracy prevalent that are civic in nature – ie. centrality of citizenship, equality of individual rights, denial of collective rights:

- Liberal democracy;

- Consociational democracy.

- Multiculturalism softens the boundaries between these two: multicultural democracy decouples state and nation, recognizes cultural rights of minorities.

- Ethnocracy: distinct but ‘diminished’ type of democracy.

- ‘Mini-model’ features:

- Ideology: ethnic nationalism;

- Institutionalization: appropriation of a state in which it exercises self-determination;

- Political principle: ethnic nation, not citizenry, shapes its symbols, laws and policies for the benefit of the nation;

- Membership: Nation includes members domiciled in the homeland and those living in the diaspora; Citizenship is separate from nationality; non-ethnic members are perceived as both non-desirable and a threat to national integrity.

- Political system: democratic. All permanent residents are citizens, but do not possess equal civic, political, legal rights: ‘defensive democracy’ (478).

- “Ethnic democracy meets the minimal and procedural definition of democracy, but it falls short of the major Western civic… democracies. It is a diminished type of democracy because it takes the ethnic nation, not the citizenry, as the cornerstone of the state and does not extend equality of rights to all. Ethnic democracy suffers from an inherent contradiction between ethnic ascendance and civic equality” (478).

- Factors conducive to emergence:

- Pre-existence of ethnic nationalism and of an ethnic nation;

- Existence of a (real or perceived) threat to the nation requiring majority mobilization;

- Majority’s commitment to democracy;

- Manageable minority size.

- Conditions for stability:

- Clear, continued numerical superiority of the ethnic nation;

- Majority’s continued sense of threat;

- Non-interference on the part of the minority’s kin-state (external homeland);

- Non-intervention against the ethnocracy by the international community.

- Three subtypes along dynamic continuum from consociational democracy to non-democracy

- ‘Hardline’ subtype: Strict control over the minority;

- ‘Standard’ subtype: in the middle;

- ‘Improved’ subtype: mild elements of conscociationalism.

- Four controversial issues:

- Conceptual adequacy: critics claim it is virtually indistinguishable from ‘Herrenvolk’ (settler) democracy because they share hegemonic control and tyranny of the majority and differ in tactics only. However, ethnic democracy meets minimal procedural definition of democracy, which requires extension of citizenship rights but not full and equal rights (481).

- Stability: critics claim it is unstable because of fundamental self-contradictions and apparent illegitimacy. However, it can be stable for a long time and transform over time to another type.

- Effectiveness: it is blamed for ineffective conflict management and for freezing internal conflicts. But it can moderate deep cleavages and is superior to other means of difference elimination (genocide, ethnic cleansing etc).

- Legitimacy: critics claim it misrepresents a non-democracy as a democracy, “thereby legitimating the illegitimate” (481) and serving as wrong normative model for democratizing states, as well as tool for justifying injustices perpetrated by non-democratic states and majorities. In fact, its legitimacy draws from both nation-state and democracy and attempts to balance them.

- Four normative ways towards legitimation – 2 pragmatic and 2 ideological:

- Ethnic democracy as lesser evil (Pragmatic 1): mode of conflict management superior to violence, domination etc.

- Ethnic democracy as temporary necessity (Pragmatic 2): could and should change later into a more acceptable type;

- Ethnic democracy is compatible with universal minority tights (Ideological 1): grants both civic and collective group rights and is compatible with extension of legal protection, affirmative action, cultural autonomy, even powersharing.

- Partial superiority over liberal democracy (Ideological 2): no truly ‘neutral’ liberal-democratic state truly exists. In ‘republican liberal democracy’ state is partial and imposes national language and culture of dominant group, assimilates immigrants.

- Israel as an ethnic democracy

- History

- 1984: 2 million persons in Palestine, one-third Jewish.

- By mid-1949, only 186,000 of the 900,000 Palestinians living in Israel still remained there (al-Naqba: the Disaster).

- Rise of PLO and struggle for peace and equality: first (1987 -93) and second (2000) Intifadas.

- Features

- A Jewish and democratic state; homeland of all Jewish people, 61% of whom live in diaspora.

- Zionism is de facto state ideology.

- Religion plays a central role: determines who is and is not a Jew.

- Membership in Jewish nation is kept separate from state citizenship.

- Law of Return: allows all Jews world-wide free admission and settlement; but no Right of Return for Palestinian refugees and their descendants;

- Virtually no immigration and naturalization for non-Jews.

- Hebrew is official language.

- Jews rule the land regime: Arab share of land is 3.5%; their municipal control of land is 2.5%.

- State symbols are strictly Jewish.

- Three major perceived threats:

- Physical and political survival of Israel in the Middle East;

- Palestinian citizens of Israel: a security and demographic hazard; loyalty issue: affiliation to the Palestinian people and a future Palestinian state;

- Menace to continued survival of the Jewish diaspora: vital for Israel’s survival.

- Diminished democracy:

- Arab rights are incomplete and not properly protected;

- Israel recognizes Arabs as a cultural minority but denies them the status of a national Palestinian-Arab minority and does not recognize their national leadership.

- Arab right to representation, protest and struggle is highly respected by the state.

- “Arabs are regarded as potentially disloyal to the state and placed under security and political control” -especially security surveillance (489); they are exempted from compulsory military service and excluded from other security forces.

- “The [Jewish” state operates in a permanent state of emergency with unlimited powers to suspend civil rights in order to detect and prevent security infractions. It denies Arabs cultural autonomy lest they misuse it for organizing against the state, building an independent power based, conducting illegal struggles and forming a secessionist movement” (489).

- Factors conducive to emergence of ethnic democracy in Israel:

- Emergence of Zionism in Eastern Europe;

- Commitment of Zionism and Jewish founders of the state to democratic values and Western orientation:

- Indispensable mode of conflict management between rival Jewish groups;

- Adherence to democratic procedures;

- Strong ideological and pragmatic considerations.

- Affordability: Arabs constituted a small and manageable minority after 1948 exodus.

- Conditions of stability

- Need to keep Jews as permanent majority in Israel;

- Ongoing sense of threat to survival of Jewish ethnic nation in Israel and abroad;

- Continued inability of Arab world and Palestinian people to intercede on behalf of the Arab minority in Israel;

- Lack of intervention by the international community on behalf of the Arab minority.

- Signs of erosion of stability conditions:

- Number on non-Jews in Israeli population is increasing;

- Rising involvement of international community in Israel’s minority affairs;

- Shift from a hardline to a standard type

- Over past five decades, Israeli democracy has improved and bettered its treatment of Arab citizens;

- Democratization has liberalized Israel and its minority policies;

- Jewish distrust of Arabs has declined to some extent;

- Rabin’s assassination in November 1995 was a big setback for Arab-Jewish relations;

- Process of deterioration in relations was accelerated by October 2000 Intifada;

- Rise of subversive and terrorist acts perpetrated by Israeli Arab citizens further distances Jews from Arabs;

- Israeli Knesset decided in May 2002 to suspend family reunions with Palestinians and to seek legal ways to curb them;

- However, there is no return to the hardline subtype of ethnic democracy.

- History

- Challenges by critics of classification of Israel as an ethnic democracy:

- Israel Supreme Court: Israel is a constitutional democracy: majority rule and human rights.

- Sheffer: Israel is almost a ‘private liberal democracy’;

- Kineret Declaration, October 2001: “there is no contradiction between Israel being a Jewish state and being a democratic state” (495);

- Avineri: Israel is a ‘republican liberal democracy’;

- Fallacy of conceptual stretching: concept of liberal democracy is distorted and stretched to fit Israel: “Yet Israel is not a liberal democracy because of the fundamental contradiction between its egalitarian universalistic-democratic character and its inegalitarian Jewish-Zionist character” (495).

- Other critics say Israel is an ethnic non-democracy: ‘Herrenvolk democracy’ (Benvenisti); ‘Ethnocracy’ (Yiftachel); fails 3 out of 4 conditions of democracy (Kimmerling);

- This disqualification of Israel as a democracy is not justified: Israel is a viable democracy meeting minimal and procedural definition of democracy.

- Occupation of West Bank and Gaza is controversial exactly because its contradicts the Jewish and democratic nature of the state;

- Israeli Arabs value democracy in Israel because it enables them to struggle for equality and full participation.

- Complex reality of Israel in Middle East: Israel is a democracy, albeit not a ‘first rate Western democracy’: rights are extended to all, but not equally; contradiction between ethnos (Jewish nation) and demos (democratic state).

Lustick, I. (1979) ‘Stability in Divided Societies: Consociationalism versus Control’

Lustick, I. (1979) ‘Stability in Divided Societies: Consociationalism versus Control’, World Politics 31 (3), 325-44.

- Focus on compromise, bargaining and accommodation as methods for achieving stability in deeply divided societies.

- Deeply divided: a situation where “ascriptive ties generate an antagonistic segmentation of society, based on terminal identities with high political salience, sustained over a substantial period of time and a wide variety of issues. As a minimum condition, boundaries between rival groups must be sharp enough so that membership is clear and, with few exceptions, unchangeable” (325).

- Aim: to distinguish between ‘consociational’ approach and ‘control’: consociational models can be deployed effectively only if an alternative typological category of ‘control’ is available.

- Puzzle: “how to explain the political stability over time in societies that continue to be characterized by deep vertical cleavages”.

- Consociation and control both assume continuation of deep divisions or vertical segmentation in societies, as well as intense rivalries between segments for key resources: they are alternative explanations for stability.

- Consociationalism: mutual cooperation of subnational elites: Stability is the result of the cooperative efforts of subculture elites “to counteract the centrifugal tendencies of cultural fragmentation” (Lijphart): elite cartel whose members have a shared interest in survival of the arena where their groups compete, and negotiate and enforce, within their groups, terms of mutually acceptable compromises: interethnic bargaining (Rothchild).

- Control: “superior power of one segment is mobilized to enforce stability by constraining the political actions and opportunities of another segment or segments” (328).

- Barry: critique of consociationalism: remedies may aggravate rather than rehabilitate; antidemocratic, manipulative nature of consociational ‘techniques’ often ignored.

- Control model: stability in a vertically segmented society is the result of sustained manipulation of subordinate segments by a superordinate segment.

- Contrasting consociation and control along seven dimensions:

Issue Consociation Control Criterion that effectively governs the authoritative allocation of resources Common denominator of groups’ interests as defined by elites Interest of superordinate segment as defined by its elite. Linkages between the two subunits Political or material exchanges: negotiations, bargains, compromises. Penetrative linkages: extracts what it needs and delivers what it thinks fit. The significance of bargaining Hard bargaining between units is a necessary fact of life Hard bargaining signifies breakdown of control & stability The role of the official regime Umpires: focus is preservation of the arena (Bailey): translate compromises into legislation & administrative procedures and enforce rules without discrimination. Legal & administrative instrument of the superordinate group; staffed by dominant group; uses discretion to benefit sub-unit it represents at expense of other unit. Normative justification for continuation espoused publicly & privately by regime’s officials General references to welfare of both subunits. Elaborate group-specific ideology – derived from history and perceived interests of dominant group. Character of central strategic problem facing subunit elites Symmetrical for each sub-unit: elites must strike bargains that do not jeopardise the integrity of the system as a whole: internal group discipline is key Asymmetric with regard to both subunits: superordinate elites devise cost-effective techniques for manipulating subordinate group; subordinate elites exploit bargaining & resistance opportunities. External focus is key. Appropriate visual metaphor: separateness, specificity, stability Delicately but securely balanced scale Puppeteer manipulating his stringed puppet. - Reasons for developing ‘control’ as analytic approach:

- Explain absence of effective politicization of subnational groups other than by questioning genuineness of groups’ cultural differentiation; superordinate group directly responsible for failure of subordinate units to produce effective political organization.

- Different kinds of coercion involving mix of coercive and non-coercive techniques that emerge in particular conditions, have different implications, are more or less attractive as prescriptive models.

- “In light of the unavoidably elitist character of consociational regimes, certain consociational societies may in fact be more closed for more citizens than societies in which a certain measure of control is exercised by, for example, a dominant majority overt the free political behavior of a subordinate minority” (334).

- Category of ‘control’ helps establish conceptual boundaries of the ‘consociational’ approach; study of mechanisms of control assists in elaboration of consociational models.

- One society can contain both kinds of relationships between its different groups.

- “In deeply divided societies where consociational techniques have not been, or cannot be, successfully employed, control may represent a model for the organisation of intergroup relations that is substantially preferable to other conceivable solutions: civil war, extermination, or deportation” (336).

- Four paths for management of communal conflict:

- Institutionalised dominance: three methods of conflict management

- Proscribe/control political expression of dominated groups’ interests;

- Prohibit entry/access of dominated group members into dominant group;

- Provide monopoly/preferential access to dominant group members to political participation, advanced education, economic opportunities etc.

- Induced assimilation;

- Syncretic integration;

- Balanced pluralism.

- Institutionalised dominance: three methods of conflict management

- Overt coercion is often evidence of breakdown of control system, not just proof of its existence (Kuper).

- Parallels with theory of ‘internal colonialism’.

- “In particular situations and for limited periods of time, certain forms of control may be preferable to the chaos and bloodshed that might be the only alternatives” (344).

- Study of ‘control’ systems helps identify strategies for resistance and is part of struggle to dismantle such systems.