O’Leary, B. and McGarry, J. (1996) ‘Exercising Control: the second Protestant Ascendancy, 1920-62’

O’Leary, B. and McGarry, J. (1996) ‘Exercising Control: the second Protestant Ascendancy, 1920-62’, in B. O’Leary and J. McGarry, eds., The Politics of Antagonism: Understanding Northern Ireland, 2. ed., London, Athlone Press, 107-52.

- Northern Ireland (‘NI’) is “the paradigm of state- and nation-building failure in western Europe” (107), as “the product of differential political power” (108).

- External environment (British imperialism and Irish irredentism) also played a key role.

- Three models of an acceptable modern state and citizenship:

- Statist: “people” are all resident adults: multicultural nation-state;

- Nationalist: all members of the nation make up the ‘people’: nation-state;

- Universalist: the entire human species is ‘the people’: global-state.

- Particularist: Only members of an ethnic group are the people: hegemonic state.

- NI between 1920 and 1972 was particularist at the sub-state level.

- “Control is ‘hegemonic’ if it makes an overtly violent ethnic contest for state power either ‘unthinkable’ or ‘unworkable’” (109); where one ethnic community dominates another by extracting the resources it requires from the subordinated one.

- NI from 1920 to 1969:

- Sovereignty formally contested between Ireland and the UK;

- Not fully integrated into either;

- Institutions lacked by-communal legitimacy;

- It was a semi-state ‘regime’ created by the UK.

- Illustration that democratic rule was compatible with tyranny of the majority: territorial, constitutional, electoral, economic, legal, cultural control were pervasive.

- Territorial control:

- Demarcation of 6 Ulster counties as NI with in-built Protestant majority;

- Gerrymandering of local government jurisdictions by UUP to drastically reduce nationalist local councils;

- Boundary commission’s terms of reference and composition were loaded against nationalists’ interests and contributed to its failure.

- Constitutional control:

- Governed under the UK Government of Ireland Act establishing a devolved parliament modelled on Westminster in Belfast:

- majoritarian government under parliamentary sovereignty unrestrained by a constitution;

- unitary form;

- concentration of executive power in one-party Cabinets;

- fusion of executive and legislative power under Cabinet dominance;

- bicameral legislature with lower house much more powerful.

- From 1920 to 1972, only UUP governments in power, characterised by Cabinet predominance: extremely stable.

- Cohesion of the Unionist bloc was key: no incentives to bargains and make concessions to nationalist minority.

- No real checks and balances: not an authentic pluralist democracy.

- Nationalist minority had little at stake in this regime.

- Legislature modeled on adversarial pattern, but parliament’s real task in NI was simply to express Unionist domination (115).

- Upper House was replica of Lower House in terms of membership: did nothing to protect minority.

- Deviated from Westminster model in 2 respects:

- Subordinate parliament could be declared unconstitutional if it violated section of the act outlawing religious discrimination (but did not extend to political opinion; offered no protection against the Special Powers Act; did not protect cultural and communal rights); and

- Proportional representation electoral system.

- No legal aid before 1965;

- Courts were unwilling to strike down Stormont legislation violating division of powers with Westminster: applied permissive ‘pith and substance’ doctrine;

- Administrative separatism:

- Westminster exercised almost no supervision or control over Stormont: NI has more the status of a ‘dominion’ than a subordinate level of local government;

- Stormont abolished Proportional representation system without Westminster interference.

- Governed under the UK Government of Ireland Act establishing a devolved parliament modelled on Westminster in Belfast:

- Electoral control – hegemonic entrenchment of UUP in government & institutionalization of ethnic divisions:

- Electoral domination of local government;

- Restriction of local franchise;

- Retention of company votes;

- Disenfranchisement of anti-UUP voters (Catholics);

- Abolition of PR (STV) and replacement with FPTP;

- Exclusion of relatively recent immigrants from the Irish Free State;

- Conservation of University constituencies;

- British voting system focusing elections on straight nationalist-unionist contest and disadvantaging smaller parties than could fragment unionist vote (125).

- Coercive control: hegemonic control must be backed by coercive resources:

- Creation of UVF (Ulster Volunteer Force), USC (Ulster Special Constabulary), RUC (Royal Ulster Constabulary) in the 1920s;

- Catholics did not join the police: RUC seen as “Protestants with guns” (126);

- Politically subordinated to the ruling party (UUP).

- Legal control:

- 1922 Civil Authorities (Special Powers) Act (permanent after 1993): draconian piece of legislation (internment without trial; arrest without warrant; curfews; prohibition of inquests; right to compel people to answer questions or be guilty of an offence…);

- 1952 Public Order Act: control non-violent forms of political opposition;

- 1954 Flags and Emblems Act: outlawed symbolic displays of nationalist allegiance.

- Overwhelmingly Protestant judiciary integrated into the UUP.

- Economic Control:

- Direct and indirect discrimination in employment and in public housing;

- Both horizontal, inter-class stratification (upper occupational classes), and horizontal, intra-class stratification (superior positions within occupations within same class), as well as vertical stratification (higher status industries and locations) favoring Protestants.

- Catholics constituted a majority of unemployed;

- UUP positioned at the center of a system of patronage.

- Administrative Control:

- Two key aspects: housing management and public employment.

- Housing segregation maintained predictable electoral outcomes and prevented development of mixed communities.

- Maintained clientelism, with UUP as an effective cross-class party.

- This is evidence of systematically organized domination and control of an ethnic group by another.

- It also shows that the Westminster model of government is compatible with hegemonic control: after 1920, NI was a particularist regime exercising hegemonic control: it seemed to be “a hermetic system which seemed incapable of change or reform” (135)

- Cultural control: Orange order marches –‘representative violence’ leading to ‘communal deterrence’ (140).

- Motivations for hegemonic control (UUP):

- Feared incorporation into a Catholic Irish nation-state (Irish nationalism & irredentism);

- Betrayal by the UK: Britain would abandon NI to the Dublin Parliament if expedient, either totally or through appeasement tactics; Unionists’ strategic dilemma: full integration with UK would make NI Protestants more British but would deprive them of tools of hegemonic control in NI and therefore more vulnerable to abandonment in future Anglo-Irish negotiations;

- Insurrection by Catholic minority: both violent (IRA) and non-violent: requires repressive security against those disloyal, so as to control them effectively: “Thus the colonial legacy was preserved into the liberal democratic era” (140).

- Fragmentation of Protestant community:

- Politics as a zero-sum game: need for strong and resilient unity;

- Fear of betrayal from within very powerful;

- Modernising Unionist elites might move away from the hegemonic control model and sense of group solidarity;

- At least Two Unionist political cultures:

- Ulster loyalist ideology: settler-ideology;

- Ulster British ideology: liberal political values refuting above.

- “The environment in which hegemonic control was maintained shows that the development and sustenance of the fears of Ulster Protestants is comprehensible without recourse to a historicist and essentialist conception of their identity” (141).

- External environment of hegemonic control:

- British state-development:

- Ill-equipped to deal with NI because of its constitutional tradition;

- NI could not be a miniature of the British political system;

- Why was NI not integrated into the British political system after 1920?

- The Anglo-Irish Treaty was regarded as the final settlement of the Irish question, and no one wanted to reopen it;

- Now Irishmen were fighting Irishmen rather than British;

- Stormont Parliament was intended to keep

Irish issues out of British politics, with reduction of Irish MPs at Westminster; - UK party competition in the 1920s and 1930s focuses on economic and class cleavages, whilst religious and territorial problems receded in importance due to the Irish settlement – thus increasing British systemic stability;

- Ambitious British politicians were no longer interested to raise Irish questions at Westminster.

- Labour refused to organize in NI: it was a place best left as a place apart.

- Tories’ ties with UUP meant they also did not want to bring about changes.

- “Hegemonic control, provided its uglier manifestations were not too visible, was preferable for British policy-makers to the known historical costs of direct intervention and management of Irish affairs”

- Integration of NI into the British state would have further soured relations with the Irish state (144).

- 1949 Ireland Act: NI remains part of the UK as long as its Parliament wants it to be. By then, hegemonic control was well entrenched, with a logic of its own (145).

- Irish nation-building failure:

- Mimetic version of British failure;

- Irish cultural nationalism reinforced the inter-Irish divide;

- Irish nationalism mirrored exclusivism and sectarianism of Ulster unionism;

- Development of Irish Free State facilitated consolidation of hegemonic control in NI by UUP;

- Fianna Fail and Fine Gael party competition in Ireland had three mutually reinforcing effects that all reinforced partition by excluding Ulster Protestants from the Irish nation;

- “Irish state-building, logically but unintentionally, took place at the expense of pan-Irish nation-building. The symmetry is evident: British state-maintenance also took place at the expense of pan-British nation-building in Northern Ireland. Hegemonic control was the joint by-product of these nation-building failures.” (147).

- British state-development:

Peleg, I. (2007) ‘Classifying Multinational States’

Peleg, I. (2007) ‘Classifying Multinational States’, in I. Peleg, Democratizing the Hegemonic State, Cambridge, CUP, 78-104.

- How does a hegemonic state (‘HS’) transform into a more inclusive polity?

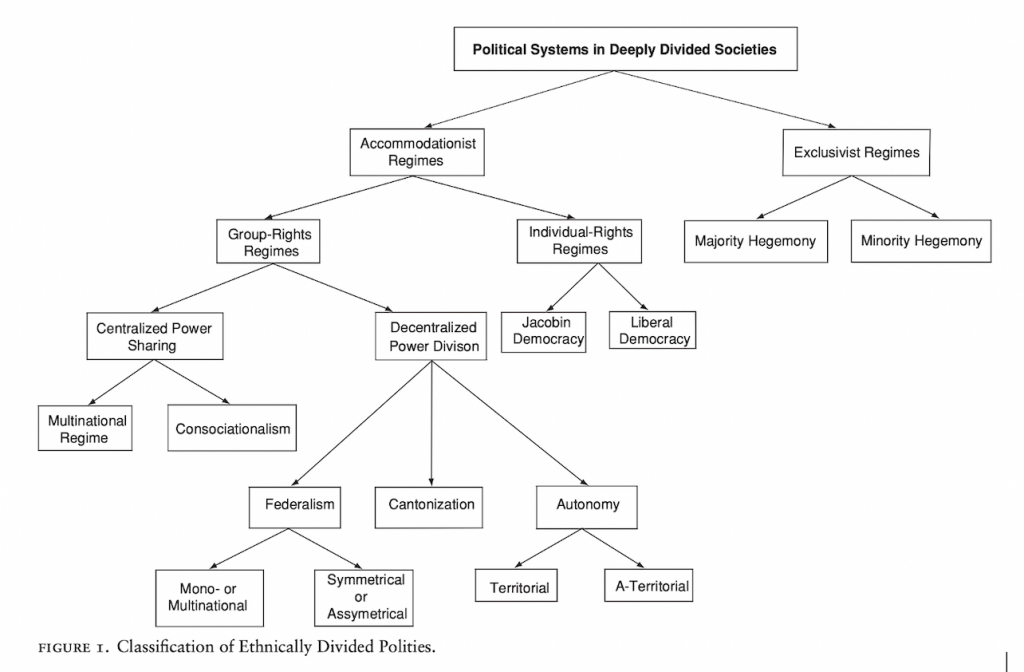

- Classificatory system with both static and dynamic components, that helps studying HSs’ potential for transformation and focuses on five modes of reaction adopted by states in deeply divided societies.

- Classification

- Key issues:

- Units being classified: societies that are deeply divided ethnically – at least two distinct groups (subjective self-identification based on enduring social constructs desired by the group or imposed by others) living within the same political space. Key question: Does the system allow dual identities? Accomodationist states vs. ethnohegemonies.

- Logic of classification: broad – deals with both democratic and non-democratic systems; each type of regime identified is both logically possible and empirically identifiable;

- Importance of classification: concerned primarily with transformation of hegemonic regimes into accommodationist systems;

- Useful classificatory system: analyses politics in deeply divided societies; however, it is oversimplified, accepts that states can adopt a mixture of policies, it is not exhaustive, and regimes can be found in combination.

- Functions of the classificatory system:

- Highlight differences between political regimes in deeply divided societies;

- Describe differences;

- Explain differences;

- Offer some prescriptions regarding possible transformation of hegemonic regimes into more accommodationist ones.

- Three key conditions:

- Empirical

- Broad

- Explicit

- Accomodationist (state-centric: recognizes its own diversity by balancing interests of various ethnic groups) vs. exclusivist (ethno-centric: enhances and perpetuates dominance of one group over the others) multinational state: what conditions allow the transformation of the latter into the former?

- States can pursue a mixture of both approaches at the same time towards various ethnic groups.

- Once accomodationism takes over as a characteristic of the state, its identification with only one ethnic group weakens and it becomes committed to either neutrality or reconciliation.

- Exclusivist regimes institutionalize the dominance of one ethnic group over all others; the ‘nation’ is more central that the state, which is merely an institutional tool of the former, whose form or design may be transformed.

- Two types of hegemonic exclusivist regimes:

- Majority-based: majority rules over a minority (ethnoocracy: Smooha); relatively informal discrimination against minority groups, especially in democracies; semi-consociational arrangements can emerge over time; can even move towards forms of liberal democracy: transformation from exclusivism to accomodationism is difficult (problem of ‘ethnic overbidding’ 88), but possible.

- Minority-based: minority rules over a majority; formal, official, explicit, public discrimination against both minority groups and individuals belonging to them; incompatible with any form of pluralism, based on brute force.

- Democratization breeds opposition to ethnic exclusivity.

- Hegemonic exclusivism can survive in the short- to medium-term, but is likely to be overthrown in the long run because it breeds radical resistance.

- Two types of accommodationist regimes:

- Individuals-rights based: all citizens are equal before the law; state is neutral towards social groups; unfriendly towards any notion of group rights: privatization of ethnicity; attempts to foster an overarching civic identity – clear preference for integration.

- Group-rights based: power-sharing and power-division variants; fully developed liberal democracies can afford recognition of some group rights.

- “[A]lthough individual-based democracy is altogether a very attractive regime, it often does not respond to the needs of all ethnic groups within a deeply divided society” (92).

- Very problematic to move from individual to group rights regimes: difficult to define authoritatively which groups are entitled to what rights.

- Individual and group rights can overlap: ex – affirmative action.

- Two types of individual-based regimes:

- Liberal democracies: favor decentralisation – USA, UK.

- Jacobin democracies: promote cultural centralism – France, Turkey; one dominant state-building ethnic group thinking of itself as ‘the nation’; have adapted over time because assimilationism is increasingly illegitimate:

- Extensive welfare states not unrelated to ethnic stratification;

- Ethnic associations benefit from governmental financial assistance;

- Regional languages experiencing a rebirth in education systems.

- “[I]n deeply divided societies the principles of liberal democracy, based on individual rights, while important and even crucial, are insufficient for creating a stable and just polity” (95): need to be complemented by group rights, based on principle of ‘diversification’.

- Different types of group-rights regimes:

- Centralised power-sharing vs. decentralised power-division regimes: both serve as modes for establishing stable interethnic regimes;

- Within power-sharing regimes (trust and cooperation), difference between consociational and bi- or multinational regimes (higher order of power-sharing; very rare): grand coalitions where elite groups make common decisions based on relatively even distribution of powers;

- Within power-division regimes (agree to avoid each other), three approaches: autonomy (both separate and shared power areas, both Territorial and non-territorial -personal, cultural- autonomy), federalism (mononational and multinational; symmetrical vs. asymmetrical), cantonization (ethnic and territorial power division to minimize ethnic conflict and maximize state cogerence): clear distribution of powers; dominant nation grants limited powers to weaker ethnicities. Hegemonic states can be transformed into accommodationist ones via various types of federalism (ex: asymmetrical), but can also lead to separatism movements and secession attempts (biethnic federations are especially fragile). Emergence of supranational bodies (ex: EU) allows for development of more creative power-sharing schemes in the future (100).

- Some believe that, in deeply divided societies, consociationalism is the only game in town; but it has very mixed track record and clear limits (outbidding: Northern Ireland).

- How do hegemonic regimes transform themselves into either individual-based or group-based accomodationism through dynamic processes of change (direction, intensity, internal/external) ?

- Seven types of potential transformation in multi-national states:

- Status quo;

- Moderate democratization;

- Radical (‘mega-constitutional’) democratization;

- Moderate (‘benign’) ethnicization;

- Radical (‘malignant’) ethnicization;

- Peaceful separation;

- Forced partition.