O’Leary, B. and McGarry, J. (1996) ‘Exercising Control: the second Protestant Ascendancy, 1920-62’

25 October 2020O’Leary, B. and McGarry, J. (1996) ‘Exercising Control: the second Protestant Ascendancy, 1920-62’, in B. O’Leary and J. McGarry, eds., The Politics of Antagonism: Understanding Northern Ireland, 2. ed., London, Athlone Press, 107-52.

- Northern Ireland (‘NI’) is “the paradigm of state- and nation-building failure in western Europe” (107), as “the product of differential political power” (108).

- External environment (British imperialism and Irish irredentism) also played a key role.

- Three models of an acceptable modern state and citizenship:

- Statist: “people” are all resident adults: multicultural nation-state;

- Nationalist: all members of the nation make up the ‘people’: nation-state;

- Universalist: the entire human species is ‘the people’: global-state.

- Particularist: Only members of an ethnic group are the people: hegemonic state.

- NI between 1920 and 1972 was particularist at the sub-state level.

- “Control is ‘hegemonic’ if it makes an overtly violent ethnic contest for state power either ‘unthinkable’ or ‘unworkable’” (109); where one ethnic community dominates another by extracting the resources it requires from the subordinated one.

- NI from 1920 to 1969:

- Sovereignty formally contested between Ireland and the UK;

- Not fully integrated into either;

- Institutions lacked by-communal legitimacy;

- It was a semi-state ‘regime’ created by the UK.

- Illustration that democratic rule was compatible with tyranny of the majority: territorial, constitutional, electoral, economic, legal, cultural control were pervasive.

- Territorial control:

- Demarcation of 6 Ulster counties as NI with in-built Protestant majority;

- Gerrymandering of local government jurisdictions by UUP to drastically reduce nationalist local councils;

- Boundary commission’s terms of reference and composition were loaded against nationalists’ interests and contributed to its failure.

- Constitutional control:

- Governed under the UK Government of Ireland Act establishing a devolved parliament modelled on Westminster in Belfast:

- majoritarian government under parliamentary sovereignty unrestrained by a constitution;

- unitary form;

- concentration of executive power in one-party Cabinets;

- fusion of executive and legislative power under Cabinet dominance;

- bicameral legislature with lower house much more powerful.

- From 1920 to 1972, only UUP governments in power, characterised by Cabinet predominance: extremely stable.

- Cohesion of the Unionist bloc was key: no incentives to bargains and make concessions to nationalist minority.

- No real checks and balances: not an authentic pluralist democracy.

- Nationalist minority had little at stake in this regime.

- Legislature modeled on adversarial pattern, but parliament’s real task in NI was simply to express Unionist domination (115).

- Upper House was replica of Lower House in terms of membership: did nothing to protect minority.

- Deviated from Westminster model in 2 respects:

- Subordinate parliament could be declared unconstitutional if it violated section of the act outlawing religious discrimination (but did not extend to political opinion; offered no protection against the Special Powers Act; did not protect cultural and communal rights); and

- Proportional representation electoral system.

- No legal aid before 1965;

- Courts were unwilling to strike down Stormont legislation violating division of powers with Westminster: applied permissive ‘pith and substance’ doctrine;

- Administrative separatism:

- Westminster exercised almost no supervision or control over Stormont: NI has more the status of a ‘dominion’ than a subordinate level of local government;

- Stormont abolished Proportional representation system without Westminster interference.

- Governed under the UK Government of Ireland Act establishing a devolved parliament modelled on Westminster in Belfast:

- Electoral control – hegemonic entrenchment of UUP in government & institutionalization of ethnic divisions:

- Electoral domination of local government;

- Restriction of local franchise;

- Retention of company votes;

- Disenfranchisement of anti-UUP voters (Catholics);

- Abolition of PR (STV) and replacement with FPTP;

- Exclusion of relatively recent immigrants from the Irish Free State;

- Conservation of University constituencies;

- British voting system focusing elections on straight nationalist-unionist contest and disadvantaging smaller parties than could fragment unionist vote (125).

- Coercive control: hegemonic control must be backed by coercive resources:

- Creation of UVF (Ulster Volunteer Force), USC (Ulster Special Constabulary), RUC (Royal Ulster Constabulary) in the 1920s;

- Catholics did not join the police: RUC seen as “Protestants with guns” (126);

- Politically subordinated to the ruling party (UUP).

- Legal control:

- 1922 Civil Authorities (Special Powers) Act (permanent after 1993): draconian piece of legislation (internment without trial; arrest without warrant; curfews; prohibition of inquests; right to compel people to answer questions or be guilty of an offence…);

- 1952 Public Order Act: control non-violent forms of political opposition;

- 1954 Flags and Emblems Act: outlawed symbolic displays of nationalist allegiance.

- Overwhelmingly Protestant judiciary integrated into the UUP.

- Economic Control:

- Direct and indirect discrimination in employment and in public housing;

- Both horizontal, inter-class stratification (upper occupational classes), and horizontal, intra-class stratification (superior positions within occupations within same class), as well as vertical stratification (higher status industries and locations) favoring Protestants.

- Catholics constituted a majority of unemployed;

- UUP positioned at the center of a system of patronage.

- Administrative Control:

- Two key aspects: housing management and public employment.

- Housing segregation maintained predictable electoral outcomes and prevented development of mixed communities.

- Maintained clientelism, with UUP as an effective cross-class party.

- This is evidence of systematically organized domination and control of an ethnic group by another.

- It also shows that the Westminster model of government is compatible with hegemonic control: after 1920, NI was a particularist regime exercising hegemonic control: it seemed to be “a hermetic system which seemed incapable of change or reform” (135)

- Cultural control: Orange order marches –‘representative violence’ leading to ‘communal deterrence’ (140).

- Motivations for hegemonic control (UUP):

- Feared incorporation into a Catholic Irish nation-state (Irish nationalism & irredentism);

- Betrayal by the UK: Britain would abandon NI to the Dublin Parliament if expedient, either totally or through appeasement tactics; Unionists’ strategic dilemma: full integration with UK would make NI Protestants more British but would deprive them of tools of hegemonic control in NI and therefore more vulnerable to abandonment in future Anglo-Irish negotiations;

- Insurrection by Catholic minority: both violent (IRA) and non-violent: requires repressive security against those disloyal, so as to control them effectively: “Thus the colonial legacy was preserved into the liberal democratic era” (140).

- Fragmentation of Protestant community:

- Politics as a zero-sum game: need for strong and resilient unity;

- Fear of betrayal from within very powerful;

- Modernising Unionist elites might move away from the hegemonic control model and sense of group solidarity;

- At least Two Unionist political cultures:

- Ulster loyalist ideology: settler-ideology;

- Ulster British ideology: liberal political values refuting above.

- “The environment in which hegemonic control was maintained shows that the development and sustenance of the fears of Ulster Protestants is comprehensible without recourse to a historicist and essentialist conception of their identity” (141).

- External environment of hegemonic control:

- British state-development:

- Ill-equipped to deal with NI because of its constitutional tradition;

- NI could not be a miniature of the British political system;

- Why was NI not integrated into the British political system after 1920?

- The Anglo-Irish Treaty was regarded as the final settlement of the Irish question, and no one wanted to reopen it;

- Now Irishmen were fighting Irishmen rather than British;

- Stormont Parliament was intended to keep

Irish issues out of British politics, with reduction of Irish MPs at Westminster; - UK party competition in the 1920s and 1930s focuses on economic and class cleavages, whilst religious and territorial problems receded in importance due to the Irish settlement – thus increasing British systemic stability;

- Ambitious British politicians were no longer interested to raise Irish questions at Westminster.

- Labour refused to organize in NI: it was a place best left as a place apart.

- Tories’ ties with UUP meant they also did not want to bring about changes.

- “Hegemonic control, provided its uglier manifestations were not too visible, was preferable for British policy-makers to the known historical costs of direct intervention and management of Irish affairs”

- Integration of NI into the British state would have further soured relations with the Irish state (144).

- 1949 Ireland Act: NI remains part of the UK as long as its Parliament wants it to be. By then, hegemonic control was well entrenched, with a logic of its own (145).

- Irish nation-building failure:

- Mimetic version of British failure;

- Irish cultural nationalism reinforced the inter-Irish divide;

- Irish nationalism mirrored exclusivism and sectarianism of Ulster unionism;

- Development of Irish Free State facilitated consolidation of hegemonic control in NI by UUP;

- Fianna Fail and Fine Gael party competition in Ireland had three mutually reinforcing effects that all reinforced partition by excluding Ulster Protestants from the Irish nation;

- “Irish state-building, logically but unintentionally, took place at the expense of pan-Irish nation-building. The symmetry is evident: British state-maintenance also took place at the expense of pan-British nation-building in Northern Ireland. Hegemonic control was the joint by-product of these nation-building failures.” (147).

- British state-development:

Peleg, I. (2007) ‘Classifying Multinational States’

Peleg, I. (2007) ‘Classifying Multinational States’, in I. Peleg, Democratizing the Hegemonic State, Cambridge, CUP, 78-104.

- How does a hegemonic state (‘HS’) transform into a more inclusive polity?

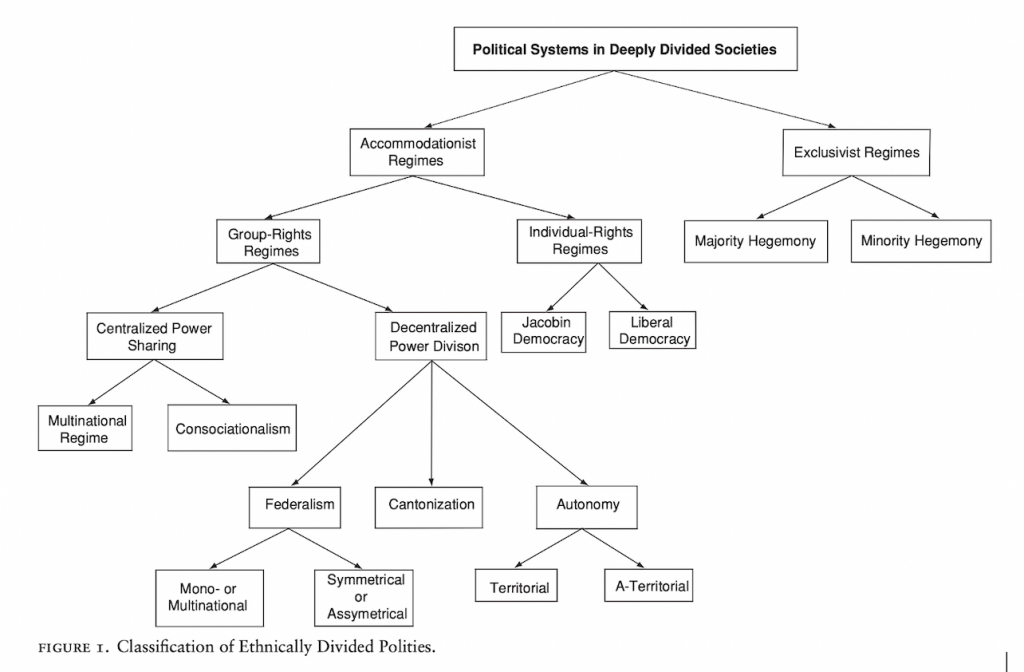

- Classificatory system with both static and dynamic components, that helps studying HSs’ potential for transformation and focuses on five modes of reaction adopted by states in deeply divided societies.

- Classification

- Key issues:

- Units being classified: societies that are deeply divided ethnically – at least two distinct groups (subjective self-identification based on enduring social constructs desired by the group or imposed by others) living within the same political space. Key question: Does the system allow dual identities? Accomodationist states vs. ethnohegemonies.

- Logic of classification: broad – deals with both democratic and non-democratic systems; each type of regime identified is both logically possible and empirically identifiable;

- Importance of classification: concerned primarily with transformation of hegemonic regimes into accommodationist systems;

- Useful classificatory system: analyses politics in deeply divided societies; however, it is oversimplified, accepts that states can adopt a mixture of policies, it is not exhaustive, and regimes can be found in combination.

- Functions of the classificatory system:

- Highlight differences between political regimes in deeply divided societies;

- Describe differences;

- Explain differences;

- Offer some prescriptions regarding possible transformation of hegemonic regimes into more accommodationist ones.

- Three key conditions:

- Empirical

- Broad

- Explicit

- Accomodationist (state-centric: recognizes its own diversity by balancing interests of various ethnic groups) vs. exclusivist (ethno-centric: enhances and perpetuates dominance of one group over the others) multinational state: what conditions allow the transformation of the latter into the former?

- States can pursue a mixture of both approaches at the same time towards various ethnic groups.

- Once accomodationism takes over as a characteristic of the state, its identification with only one ethnic group weakens and it becomes committed to either neutrality or reconciliation.

- Exclusivist regimes institutionalize the dominance of one ethnic group over all others; the ‘nation’ is more central that the state, which is merely an institutional tool of the former, whose form or design may be transformed.

- Two types of hegemonic exclusivist regimes:

- Majority-based: majority rules over a minority (ethnoocracy: Smooha); relatively informal discrimination against minority groups, especially in democracies; semi-consociational arrangements can emerge over time; can even move towards forms of liberal democracy: transformation from exclusivism to accomodationism is difficult (problem of ‘ethnic overbidding’ 88), but possible.

- Minority-based: minority rules over a majority; formal, official, explicit, public discrimination against both minority groups and individuals belonging to them; incompatible with any form of pluralism, based on brute force.

- Democratization breeds opposition to ethnic exclusivity.

- Hegemonic exclusivism can survive in the short- to medium-term, but is likely to be overthrown in the long run because it breeds radical resistance.

- Two types of accommodationist regimes:

- Individuals-rights based: all citizens are equal before the law; state is neutral towards social groups; unfriendly towards any notion of group rights: privatization of ethnicity; attempts to foster an overarching civic identity – clear preference for integration.

- Group-rights based: power-sharing and power-division variants; fully developed liberal democracies can afford recognition of some group rights.

- “[A]lthough individual-based democracy is altogether a very attractive regime, it often does not respond to the needs of all ethnic groups within a deeply divided society” (92).

- Very problematic to move from individual to group rights regimes: difficult to define authoritatively which groups are entitled to what rights.

- Individual and group rights can overlap: ex – affirmative action.

- Two types of individual-based regimes:

- Liberal democracies: favor decentralisation – USA, UK.

- Jacobin democracies: promote cultural centralism – France, Turkey; one dominant state-building ethnic group thinking of itself as ‘the nation’; have adapted over time because assimilationism is increasingly illegitimate:

- Extensive welfare states not unrelated to ethnic stratification;

- Ethnic associations benefit from governmental financial assistance;

- Regional languages experiencing a rebirth in education systems.

- “[I]n deeply divided societies the principles of liberal democracy, based on individual rights, while important and even crucial, are insufficient for creating a stable and just polity” (95): need to be complemented by group rights, based on principle of ‘diversification’.

- Different types of group-rights regimes:

- Centralised power-sharing vs. decentralised power-division regimes: both serve as modes for establishing stable interethnic regimes;

- Within power-sharing regimes (trust and cooperation), difference between consociational and bi- or multinational regimes (higher order of power-sharing; very rare): grand coalitions where elite groups make common decisions based on relatively even distribution of powers;

- Within power-division regimes (agree to avoid each other), three approaches: autonomy (both separate and shared power areas, both Territorial and non-territorial -personal, cultural- autonomy), federalism (mononational and multinational; symmetrical vs. asymmetrical), cantonization (ethnic and territorial power division to minimize ethnic conflict and maximize state cogerence): clear distribution of powers; dominant nation grants limited powers to weaker ethnicities. Hegemonic states can be transformed into accommodationist ones via various types of federalism (ex: asymmetrical), but can also lead to separatism movements and secession attempts (biethnic federations are especially fragile). Emergence of supranational bodies (ex: EU) allows for development of more creative power-sharing schemes in the future (100).

- Some believe that, in deeply divided societies, consociationalism is the only game in town; but it has very mixed track record and clear limits (outbidding: Northern Ireland).

- How do hegemonic regimes transform themselves into either individual-based or group-based accomodationism through dynamic processes of change (direction, intensity, internal/external) ?

- Seven types of potential transformation in multi-national states:

- Status quo;

- Moderate democratization;

- Radical (‘mega-constitutional’) democratization;

- Moderate (‘benign’) ethnicization;

- Radical (‘malignant’) ethnicization;

- Peaceful separation;

- Forced partition.

Smooha, S. (2002) ‘The model of ethnic democracy: Israel as a Jewish and democratic state’

Smooha, S. (2002) ‘The model of ethnic democracy: Israel as a Jewish and democratic state’, Nations and Nationalism 8 (4), 475-503.

- Liberal nation-state in decline in West: shift towards multicultural civic democracy.

- Outside west, other countries are consolidating non-civic form of democracy subservient to a single ethnic nation: ethnic democracy or ‘ethnocracy’. Ex: Israel.

- Two main forms of democracy prevalent that are civic in nature – ie. centrality of citizenship, equality of individual rights, denial of collective rights:

- Liberal democracy;

- Consociational democracy.

- Multiculturalism softens the boundaries between these two: multicultural democracy decouples state and nation, recognizes cultural rights of minorities.

- Ethnocracy: distinct but ‘diminished’ type of democracy.

- ‘Mini-model’ features:

- Ideology: ethnic nationalism;

- Institutionalization: appropriation of a state in which it exercises self-determination;

- Political principle: ethnic nation, not citizenry, shapes its symbols, laws and policies for the benefit of the nation;

- Membership: Nation includes members domiciled in the homeland and those living in the diaspora; Citizenship is separate from nationality; non-ethnic members are perceived as both non-desirable and a threat to national integrity.

- Political system: democratic. All permanent residents are citizens, but do not possess equal civic, political, legal rights: ‘defensive democracy’ (478).

- “Ethnic democracy meets the minimal and procedural definition of democracy, but it falls short of the major Western civic… democracies. It is a diminished type of democracy because it takes the ethnic nation, not the citizenry, as the cornerstone of the state and does not extend equality of rights to all. Ethnic democracy suffers from an inherent contradiction between ethnic ascendance and civic equality” (478).

- Factors conducive to emergence:

- Pre-existence of ethnic nationalism and of an ethnic nation;

- Existence of a (real or perceived) threat to the nation requiring majority mobilization;

- Majority’s commitment to democracy;

- Manageable minority size.

- Conditions for stability:

- Clear, continued numerical superiority of the ethnic nation;

- Majority’s continued sense of threat;

- Non-interference on the part of the minority’s kin-state (external homeland);

- Non-intervention against the ethnocracy by the international community.

- Three subtypes along dynamic continuum from consociational democracy to non-democracy

- ‘Hardline’ subtype: Strict control over the minority;

- ‘Standard’ subtype: in the middle;

- ‘Improved’ subtype: mild elements of conscociationalism.

- Four controversial issues:

- Conceptual adequacy: critics claim it is virtually indistinguishable from ‘Herrenvolk’ (settler) democracy because they share hegemonic control and tyranny of the majority and differ in tactics only. However, ethnic democracy meets minimal procedural definition of democracy, which requires extension of citizenship rights but not full and equal rights (481).

- Stability: critics claim it is unstable because of fundamental self-contradictions and apparent illegitimacy. However, it can be stable for a long time and transform over time to another type.

- Effectiveness: it is blamed for ineffective conflict management and for freezing internal conflicts. But it can moderate deep cleavages and is superior to other means of difference elimination (genocide, ethnic cleansing etc).

- Legitimacy: critics claim it misrepresents a non-democracy as a democracy, “thereby legitimating the illegitimate” (481) and serving as wrong normative model for democratizing states, as well as tool for justifying injustices perpetrated by non-democratic states and majorities. In fact, its legitimacy draws from both nation-state and democracy and attempts to balance them.

- Four normative ways towards legitimation – 2 pragmatic and 2 ideological:

- Ethnic democracy as lesser evil (Pragmatic 1): mode of conflict management superior to violence, domination etc.

- Ethnic democracy as temporary necessity (Pragmatic 2): could and should change later into a more acceptable type;

- Ethnic democracy is compatible with universal minority tights (Ideological 1): grants both civic and collective group rights and is compatible with extension of legal protection, affirmative action, cultural autonomy, even powersharing.

- Partial superiority over liberal democracy (Ideological 2): no truly ‘neutral’ liberal-democratic state truly exists. In ‘republican liberal democracy’ state is partial and imposes national language and culture of dominant group, assimilates immigrants.

- Israel as an ethnic democracy

- History

- 1984: 2 million persons in Palestine, one-third Jewish.

- By mid-1949, only 186,000 of the 900,000 Palestinians living in Israel still remained there (al-Naqba: the Disaster).

- Rise of PLO and struggle for peace and equality: first (1987 -93) and second (2000) Intifadas.

- Features

- A Jewish and democratic state; homeland of all Jewish people, 61% of whom live in diaspora.

- Zionism is de facto state ideology.

- Religion plays a central role: determines who is and is not a Jew.

- Membership in Jewish nation is kept separate from state citizenship.

- Law of Return: allows all Jews world-wide free admission and settlement; but no Right of Return for Palestinian refugees and their descendants;

- Virtually no immigration and naturalization for non-Jews.

- Hebrew is official language.

- Jews rule the land regime: Arab share of land is 3.5%; their municipal control of land is 2.5%.

- State symbols are strictly Jewish.

- Three major perceived threats:

- Physical and political survival of Israel in the Middle East;

- Palestinian citizens of Israel: a security and demographic hazard; loyalty issue: affiliation to the Palestinian people and a future Palestinian state;

- Menace to continued survival of the Jewish diaspora: vital for Israel’s survival.

- Diminished democracy:

- Arab rights are incomplete and not properly protected;

- Israel recognizes Arabs as a cultural minority but denies them the status of a national Palestinian-Arab minority and does not recognize their national leadership.

- Arab right to representation, protest and struggle is highly respected by the state.

- “Arabs are regarded as potentially disloyal to the state and placed under security and political control” -especially security surveillance (489); they are exempted from compulsory military service and excluded from other security forces.

- “The [Jewish” state operates in a permanent state of emergency with unlimited powers to suspend civil rights in order to detect and prevent security infractions. It denies Arabs cultural autonomy lest they misuse it for organizing against the state, building an independent power based, conducting illegal struggles and forming a secessionist movement” (489).

- Factors conducive to emergence of ethnic democracy in Israel:

- Emergence of Zionism in Eastern Europe;

- Commitment of Zionism and Jewish founders of the state to democratic values and Western orientation:

- Indispensable mode of conflict management between rival Jewish groups;

- Adherence to democratic procedures;

- Strong ideological and pragmatic considerations.

- Affordability: Arabs constituted a small and manageable minority after 1948 exodus.

- Conditions of stability

- Need to keep Jews as permanent majority in Israel;

- Ongoing sense of threat to survival of Jewish ethnic nation in Israel and abroad;

- Continued inability of Arab world and Palestinian people to intercede on behalf of the Arab minority in Israel;

- Lack of intervention by the international community on behalf of the Arab minority.

- Signs of erosion of stability conditions:

- Number on non-Jews in Israeli population is increasing;

- Rising involvement of international community in Israel’s minority affairs;

- Shift from a hardline to a standard type

- Over past five decades, Israeli democracy has improved and bettered its treatment of Arab citizens;

- Democratization has liberalized Israel and its minority policies;

- Jewish distrust of Arabs has declined to some extent;

- Rabin’s assassination in November 1995 was a big setback for Arab-Jewish relations;

- Process of deterioration in relations was accelerated by October 2000 Intifada;

- Rise of subversive and terrorist acts perpetrated by Israeli Arab citizens further distances Jews from Arabs;

- Israeli Knesset decided in May 2002 to suspend family reunions with Palestinians and to seek legal ways to curb them;

- However, there is no return to the hardline subtype of ethnic democracy.

- History

- Challenges by critics of classification of Israel as an ethnic democracy:

- Israel Supreme Court: Israel is a constitutional democracy: majority rule and human rights.

- Sheffer: Israel is almost a ‘private liberal democracy’;

- Kineret Declaration, October 2001: “there is no contradiction between Israel being a Jewish state and being a democratic state” (495);

- Avineri: Israel is a ‘republican liberal democracy’;

- Fallacy of conceptual stretching: concept of liberal democracy is distorted and stretched to fit Israel: “Yet Israel is not a liberal democracy because of the fundamental contradiction between its egalitarian universalistic-democratic character and its inegalitarian Jewish-Zionist character” (495).

- Other critics say Israel is an ethnic non-democracy: ‘Herrenvolk democracy’ (Benvenisti); ‘Ethnocracy’ (Yiftachel); fails 3 out of 4 conditions of democracy (Kimmerling);

- This disqualification of Israel as a democracy is not justified: Israel is a viable democracy meeting minimal and procedural definition of democracy.

- Occupation of West Bank and Gaza is controversial exactly because its contradicts the Jewish and democratic nature of the state;

- Israeli Arabs value democracy in Israel because it enables them to struggle for equality and full participation.

- Complex reality of Israel in Middle East: Israel is a democracy, albeit not a ‘first rate Western democracy’: rights are extended to all, but not equally; contradiction between ethnos (Jewish nation) and demos (democratic state).

Lustick, I. (1979) ‘Stability in Divided Societies: Consociationalism versus Control’

Lustick, I. (1979) ‘Stability in Divided Societies: Consociationalism versus Control’, World Politics 31 (3), 325-44.

- Focus on compromise, bargaining and accommodation as methods for achieving stability in deeply divided societies.

- Deeply divided: a situation where “ascriptive ties generate an antagonistic segmentation of society, based on terminal identities with high political salience, sustained over a substantial period of time and a wide variety of issues. As a minimum condition, boundaries between rival groups must be sharp enough so that membership is clear and, with few exceptions, unchangeable” (325).

- Aim: to distinguish between ‘consociational’ approach and ‘control’: consociational models can be deployed effectively only if an alternative typological category of ‘control’ is available.

- Puzzle: “how to explain the political stability over time in societies that continue to be characterized by deep vertical cleavages”.

- Consociation and control both assume continuation of deep divisions or vertical segmentation in societies, as well as intense rivalries between segments for key resources: they are alternative explanations for stability.

- Consociationalism: mutual cooperation of subnational elites: Stability is the result of the cooperative efforts of subculture elites “to counteract the centrifugal tendencies of cultural fragmentation” (Lijphart): elite cartel whose members have a shared interest in survival of the arena where their groups compete, and negotiate and enforce, within their groups, terms of mutually acceptable compromises: interethnic bargaining (Rothchild).

- Control: “superior power of one segment is mobilized to enforce stability by constraining the political actions and opportunities of another segment or segments” (328).

- Barry: critique of consociationalism: remedies may aggravate rather than rehabilitate; antidemocratic, manipulative nature of consociational ‘techniques’ often ignored.

- Control model: stability in a vertically segmented society is the result of sustained manipulation of subordinate segments by a superordinate segment.

- Contrasting consociation and control along seven dimensions:

Issue Consociation Control Criterion that effectively governs the authoritative allocation of resources Common denominator of groups’ interests as defined by elites Interest of superordinate segment as defined by its elite. Linkages between the two subunits Political or material exchanges: negotiations, bargains, compromises. Penetrative linkages: extracts what it needs and delivers what it thinks fit. The significance of bargaining Hard bargaining between units is a necessary fact of life Hard bargaining signifies breakdown of control & stability The role of the official regime Umpires: focus is preservation of the arena (Bailey): translate compromises into legislation & administrative procedures and enforce rules without discrimination. Legal & administrative instrument of the superordinate group; staffed by dominant group; uses discretion to benefit sub-unit it represents at expense of other unit. Normative justification for continuation espoused publicly & privately by regime’s officials General references to welfare of both subunits. Elaborate group-specific ideology – derived from history and perceived interests of dominant group. Character of central strategic problem facing subunit elites Symmetrical for each sub-unit: elites must strike bargains that do not jeopardise the integrity of the system as a whole: internal group discipline is key Asymmetric with regard to both subunits: superordinate elites devise cost-effective techniques for manipulating subordinate group; subordinate elites exploit bargaining & resistance opportunities. External focus is key. Appropriate visual metaphor: separateness, specificity, stability Delicately but securely balanced scale Puppeteer manipulating his stringed puppet. - Reasons for developing ‘control’ as analytic approach:

- Explain absence of effective politicization of subnational groups other than by questioning genuineness of groups’ cultural differentiation; superordinate group directly responsible for failure of subordinate units to produce effective political organization.

- Different kinds of coercion involving mix of coercive and non-coercive techniques that emerge in particular conditions, have different implications, are more or less attractive as prescriptive models.

- “In light of the unavoidably elitist character of consociational regimes, certain consociational societies may in fact be more closed for more citizens than societies in which a certain measure of control is exercised by, for example, a dominant majority overt the free political behavior of a subordinate minority” (334).

- Category of ‘control’ helps establish conceptual boundaries of the ‘consociational’ approach; study of mechanisms of control assists in elaboration of consociational models.

- One society can contain both kinds of relationships between its different groups.

- “In deeply divided societies where consociational techniques have not been, or cannot be, successfully employed, control may represent a model for the organisation of intergroup relations that is substantially preferable to other conceivable solutions: civil war, extermination, or deportation” (336).

- Four paths for management of communal conflict:

- Institutionalised dominance: three methods of conflict management

- Proscribe/control political expression of dominated groups’ interests;

- Prohibit entry/access of dominated group members into dominant group;

- Provide monopoly/preferential access to dominant group members to political participation, advanced education, economic opportunities etc.

- Induced assimilation;

- Syncretic integration;

- Balanced pluralism.

- Institutionalised dominance: three methods of conflict management

- Overt coercion is often evidence of breakdown of control system, not just proof of its existence (Kuper).

- Parallels with theory of ‘internal colonialism’.

- “In particular situations and for limited periods of time, certain forms of control may be preferable to the chaos and bloodshed that might be the only alternatives” (344).

- Study of ‘control’ systems helps identify strategies for resistance and is part of struggle to dismantle such systems.

McGarry, J., O’Leary, B., and Simeon, R. (2008) ‘Integration or Accommodation? The Enduring Debate in Conflict Regulation’

McGarry, J., O’Leary, B., and Simeon, R. (2008) ‘Integration or Accommodation? The Enduring Debate in Conflict Regulation’, in S. Choudhry, ed., Constitutional Design for Divided Societies: Integration or Accommodation? Oxford, OUP, 41-88.

- Democratic states managing deep diversity can adopt two strategic approaches: either integration – promotion of a single public identity across the state’s territory (‘bridging capital’) coupled with acceptance of collective diversity in private realms (‘bonding capital’) – or accommodation – acceptance of multiple public identities and respect for cultural and regional differences – as tools of public policy. They both reject coercive assimilation.

- Assimilationists seek the erosion of private cultural and other differences as well as the creation of a common public identity, through either fusion or acculturation, in the name of ‘nation-building’: they are often ‘benevolent paternalists’ (J.S. Mill).

Integration

- Main aim: equal citizenship. It turns a blind eye to difference for public purposes (privatization of ethno-cultural differences – B. Barry) to eliminate political instability and conflict.

- Reject ethnic political parties or civic associations – prefer parties on redistributionist continuum, not recognition one and any form of autonomy based on group identities.

- Three types:

- Republicans:

- support civic nation-state, integral nationalism, sharp laicity;

- veer towards assimilationism;

- favor unitary state, majoritarian or winner-take-all political institutions, centralization and a nation-building executive;

- oppose federalism, decentralization, judicial review, ethnic-based political parties in the name of undiluted popular sovereignty.

- Liberals:

- champion nation-state and liberal institutions focusing on the individual and on values of choice and freedom, as well as meritocracy.

- incline towards soft multiculturalism but reject ethnofederalism;

- value political competition and system of checks and balances, bill of rights, judicial review, separation of powers, functional

- federalism;

- Socialists:

- state as driver towards socialist civilisation / or barrier to it!

- focus on social classes and distributive justice through substantive social citizenship; much less focus on ‘nation’ as key unit of solidarity: constitutional patriotism instead;

- promote bottom-up, mass-based collective action and civil society organisations to develop social solidarity and commonality of interests.

- Republicans:

- Usually the norm in long-established democracies in the Euro-American sphere; often associated with large majorities or territorially dispersed minorities, but not with large minorities that are territorially concentrated.

Accommodation

- Requires recognition of ethno-cultural diversity within a state, and aims at peaceful coexistence od difference communities: ‘responsible realism’, but also ‘Herderians’.

- Not primordialists, but believers in the empirically testable existence of resilient, durable, hard ethno-cultural and linguistic identities and divisions; therefore support adaptation, adjustment, and consideration of special group interests to promote loyalty to the state. (53).

- Main forms:

- Centripetalism (D. Horowitz): convergence / centrism; promote crosscutting politics and transethnic identities;

- votepooling electoral systems facilitating election of moderate politicians through campaigns appealing to centrist moderate voters in heterogenous constituencies;

- against PR systems with no or no thresholds and party lists, as well as STV in multi-member constituencies;

- appeals to rationality of politicians.

- prefers two particular electoral systems: territorially redistributive (Presidential Electoral College); and alternative vote for both legislative and presidential systems;

- favors federalism; regional majorities, asymmetrical autonomy arrangements.

- Multiculturalism (K. Renner & O. Bauer): Protection and maintenance of multiple communities in both public and private realms;

- North America and Europe do not have practice real multi-culturalism: toleration differences in private domains and promote integration in public domains as well as some minority language services, so as to help minorities adapt to dominant society.

- NA&E M remains heavily liberal and tends to be more unicultural than it pretends to be: emphasizes voluntary and fluid group memberships.

- ‘boutique multiculturalism’ (S. Fish): resistance to different culture at the point it matters most to its committed members. “Such multiculturalism is, in our view, “pseudo multiculturalism”.

It is liberal integration in disguise” (57). - Credible multiculturalist arrangements involve:

- Respect for a group’s self-government in matters the group defines as important; plus proportional representation of all groups in key public institutions;

- Share of public power through consociational arrangements;

- Territorially-based communities share public power through pluralist federations or pluralist union states respectful of historic nationalities, languages, religions.

- All require public support through legislation or expenditures.

- Consociation (A. Lijphart): addresses deep antagonisms with executive power sharing and minority vetoes, in addition to autonomy and proportionality.

- Cross-community power-sharing executive staffed by representative elites from different communities (usually grand coalition); there are ‘complete’, ‘concurrent’ and ‘plurality’ consociations;

- Mandates the principles of proportionality in executive, legislature, judiciary, elite levels of bureaucracy, police service, army – in both elected and unelected positions, as well as in electoral systems (both list-based and STV).

- Autonomy or community self-government: recognises parallel societies, equal but different, and rejects hierarchical ranking of groups; can be functional autonomy or take on territorial form; mandates public support for maintenance of diverse communities over time (therefore different from Western ‘pseudo-multiculturalism’);

- Rigid consociations in very antagonistic environments may endow each partner with veto rights, in case they perceive their fundamental interests as threatened; veto rights can be asymmetric (do not block others from pursuing certain policies) and symmetric (block all parties to do so).

- Can be democratic or undemocratic, formal or informal, liberal or corporate.

- Territorial pluralism:

- Communities that are territorially concentrated and ethnically / nationally mobilised can be managed either in a pluralist federation (internal boundaries respecting ethnicity) of pluralist union state;

- Full pluralist federations have 3 complementary arrangements:

- Significant and constitutionally entrenched autonomy for federative entities, that cannot be rescinded unilaterally by the federal government;

- Consensual, even consociational, rather than majoritarian decision-making rules within federal government, including executive power sharing and proportional principles of representation; they have strong second chambers representing the regions, strong regional judiciaries, and regional role in selecting federal judges;

- Plurinational: they recognise a pluralist rather than monist conception of sovereignty, recognised in the state’s constitution, state symbols, official languages etc; they involve collective territorial autonomy for partner nations and may permit asymmetric institutional arrangements. When autonomous and asymmetric institutions are entrenched the result is a federacy (ex: Northern Ireland if Belfast Agreement fully implemented) (66).

- However, it cannot meet adequately the needs of communities that extend beyond the state’s borders: crossborder institutions are required., ranging from functional cooperation to confederal institutions (66). “Comprehensive accommodation encompasses interstate institutions as well as intrastate institutions.

- Centripetalism (D. Horowitz): convergence / centrism; promote crosscutting politics and transethnic identities;

Engagements between integrationists and accommodationists

- The approaches lie on a continuum stretching from assimilation to disintegration.

- Significant debate between various positions (in particular between centripetalists and consociationalists) regarding which approach best contributes to secure the three fundamental sets of values grouped around stability, justice, and democracy.

- Stability:

- opposition between integrationists (charging elite-driven deepening divisions and instability justified by exaggerated ‘ancient hatreds’ and internal group homogeneity) and accomodationists (charging creation of an unstable equilibrium that will either degenerate into assimilationism or evolve into power-sharing);

- also between centripetalists (charging that elite leaders will not compromise enough because if they do they will be ‘outbid’ by more radical parties, and that ‘grand coalitions are both undemocratic and unworkable) and consociationalists (charging that reliance on outside forces to implement centripetalism as well as emphasis on votepooling as unrealistic and unlikely to bring out stability) -who agree, however, that accommodation is preferable to integration;

- Distributive Justice:

- debate between integrationists (charging that recognizing public groups as political actors may lead to internal group repression and discrimination grounded in ascriptive factors, including unfair treatment of regional minorities and unjust resource distribution) and accomodationists (charging that beneath veneer of integrationalism hides “merely assimilation with good manners” (80) privileging the majority or largest group over others) regarding the social justice of their recommendations.

- Democracy:

- Both integrationists (charge that accomodationists undermine democracy by surrendering public power to unaccountable ‘cartels’ of interest groups elites) and accomodationists (charging that majority rule in divided places is likely to be partisan rule by an actual minority of voters) regard their own solutions as more democratic than rival ones.

When is integration or accommodation appropriate?

- Today’s democratic states are limited normatively and practically to variants of integration and accommodation, since rival strategies based on assimilation, control, partition, ethnic expulsions are no longer acceptable.

- Integration is till the preferred choice in Western states, but accommodation strategies are gaining ground.

- Integration is most effective for societies where social cleavages are crosscutting rather than reinforcing, as well as in places with numerically small, territorially dispersed minorities that do not claim specific ‘historical homelands’.

- Territorial accommodation works best for middle-sized minorities concentrated in their own national space. Large, nationally mobilised minorities will tend to demand not just autonomy, but power-sharing arrangements within the federal government.

- Consociation is demanded by territorially dispersed and interspersed minorities with deeply polarised politics. In such cases, centripetalism has few chances of succeeding.

- Transstate settlements are required where national communities spill over state boundaries. Such transstate settlements are difficult to imagine, but they may become more feasible when the relevant states participate within an overarching institutional framework, such as the European Union” (87).

- “The mobilization power of a community partly shapes its orientation towards either integration or accommodation” (88).

- “In general, integration is the politics of the historically weak or the newly arrived, whereas accommodation shapes the politics of those powerful enough to resist assimilation but not strong enough to achieve secession” (88).

Weber, E. (1976) ‘Civilizing in Earnest: Schools and Schooling’

Weber, E. (1976) ‘Civilizing in Earnest: Schools and Schooling’, in E. Weber, Peasants into Frenchmen: The Modernization of Modern France, 1870-1914, Stanford, Stanford University Press, Chapter 18, 303-38.

- Village school is considered ultimate acculturation process that “made the French people French” in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, under the Third Republic (303).

- “It was only when what the schools taught made sense that they became important to those they had to teach” (303).

- Early 19th century French schools were rudimentary and improvised, with unqualified and unprofessional teachers; most students simply learned by rote.

- Francois Guizot’s 1833 education law set the foundations of France’s modern school system and in particular of public education.

- In 1881-6, Jules Ferry instituted compulsory free public elementary education, along with an elementary teaching program and inspection and control provisions. This coincided with a majority of adults speaking French, not only patois.

- By the 1890s, more girls and women were schooled and were learning French.

- In the 1880s schools experienced both better-trained teachers and more relevant curriculums.

- As regional inequalities began to disappear in the 1890s, “another step in cultural homogenization was being taken” (323).

- Improved behavior, morality and hygiene were also attributed to schools.

- Schooling became a major agent of acculturation in shaping individuals to fit into the broader national community and develop sentiments of a new patriotism: a ‘unity of spirit’ toward their fatherland – France by adopting a ‘national pedagogy’, especially in history and geography courses (330-3).

- The new schools played a critical role in national integration, national cohesion and acceptance of definition of a good citizen’s duty as being “to serve his country and to defend the fatherland” (336).

- “Like migration, politics, and economic development, school brought suggestions of alternative values and hierarchies; and of commitments to other bodies than the local group. Thy eased individuals out of the latter’s grip and shattered the hold of unchallenged cultural and political creeds – but only to train their votaries for another faith” (338).

Vidmar, J. (2010) ‘The Right of Self-Determination and Multiparty Democracy: Two Sides of the Same Coin?’

Vidmar, J. (2010) ‘The Right of Self-Determination and Multiparty Democracy: Two Sides of the Same Coin?’, Human Rights Law Review 10 (2), 239-68.

- Exploration of relationship between right of self-determination (‘SD’) and multiparty democratic political systems (‘MDPP’).

- In contemporary International Law (‘IL’), SD is not an absolute legal principle, but a human right subject to several limitations.

- MDPP is neither necessary nor sufficient condition for SD.

- Representative government principle underlies both democracy (‘D’) and SD. D & SD are associated in western European and American traditions; in eastern Europe it is rooted in 19th century nationalism.

- SD therefore refers both to a state’s internal political organisation (‘ISD’) and to external creation of new states (‘ESD’).

- Woodrow Wilson combined ISD and ESD in his 8. January 1918 ’14 Points’ speech, which made them seemingly contradictory and difficult to implement in practice.

- Until 1945, SD remained a political principle. With the UN Charter, it became a human right subject to limitations – first and foremost, to the principle of territorial integrity of States (‘TIS’).

- Therefore, in no-colonial situations, SD is consummated as ISD. Because of the requirement of representative democracy, SD became linked again to an emergent ‘right to democracy’.

- Right to participation and SD are interdependent but this does not necessarily imply an obligation to implement MDPPs.

- In IL, even governments that do not come to power through multiparty electoral contests can be seen as representative of their peoples.

- MDPPs do not automatically lead to the right of SD.

SD: Development, Democratic Pedigree, Limitations

- Both Wilson and Lenin were advocates of SD from ideologically opposite perspectives.

- For Lenin, SD was linked to secession as a path to socialist revolution.

- Wilson’s support for SD was based on the liberal principle of self-government: it was the logical corollary of popular sovereignty and consent of the governed. SD was thus a synonym for a democratic political system (244).

- In his 14 Points speech, Wilson stipulated SD as the criterion for Europe’s new states, along ethnic lines, and as resulting in the right of each nation to its own State.

- ISD and ESD could not be easily reconciled because it implied SD must be a continuous process synonymous with democratic forms of government.

- For Wilson SD was an absolute political principle; yet post-WWI events showed it had to be reconciled with the TIS principle.

- SD remained a political principle until it was codified as a human right by the 1966 ICCPR, Art. 1 and the ICSECR and declared to be accepted as part of customary international law.

- It remains subjects to same limitations as other human rights, including especially TIS.

- Only colonial SD was recognised as legitimately leading to independence and statehood.

- ‘Safeguard clause’ of the 1970 Declaration on Principles of International Law (‘DPIL’) defines TIS and can be read both as a shift from ESD to ISD, and as including an external dimension: a state without government representing all its citizens may be denied right to assert TIS principle – which would legitimize ESD claims from its national groups (confirmed in the SCC’s Quebec case): confirmation of remedial secession doctrine.

- SD is linked here with both democracy and human rights.

- However, SD “does not have an exclusive democratic pedigree” (247). Some interpret the ‘safeguard clause’ as requiring MDPPs.

SD, Governmental Representativeness and Multiparty Democracy

- The ‘safeguard clause’ requires a representative government. That does not mean it demands democratic governments, and even less MDPPs.

- The ICJ held in the 1972 East Pakistan case that in defining ‘peoples’ for the purpose of SD, one must keep in mind that “a people begin to exist only when it becomes conscious of its own identity and asserts its will to exist” (249), and therefore that SD is a political phenomenon and the exercise of the SD right is a political act.

- UNESCO sets following criteria (250), which do not include affiliation to political parties:

- Common historical tradition;

- Racial or ethnic identity;

- Cultural homogeneity;

- Linguistic unity;

- Religious or ideological affinity;

- Territorial connection;

- Common economic life.

- In practice, Southern Rhodesia’s 1965 unilateral declaration of independence was not recognised by the UN because its government did not represent all its people and declared it an “illegal regime” in its 1970 Resolution 227 because of its racial animus.

- However, the democratic principles referred to here related to popular support for change of legal status of a territory, not to MDPPs.

- The South African bantoustans granted quasi-independence by South Africa between 1976 and 1981 were also not recognised by the UN and constituted a violation of SD right of South African people grounded in racism and apartheid. Security Council Resolution 417 also asserted that South Africa’s entire apartheid system was racist and violated the SD right of its people; it did not focus on lack of MDPP.

- Collective practice of UN organs shows that even governments that do not emerge via MDPPs may be considered legitimate and representative of their peoples.

- When the DPIL was adopted in 1970, it was clear that political representativeness did not demand exclusively MDPPs.

- Security Council resolution never denied states legitimacy on democratic grounds because of non-elected governments; therefore, “governmental legitimacy in international law is not linked to a democratic political process”.

- IL does not prescribe how ISD should be implemented by states with their territories and accepts it can take various forms.

The Right of SD, Political Participation and the Choice of a Political System

- Interdependence between SD right and Political participation right also does not result in a requirement of MDPP; nor do actually existing MDPPs lead to an automatic realization of the right of SD.

- Some authors and politicians claim that SD right requires adherence to ”some democratic standards” based on Art. 25 ICCPR elaborating right to political participation.

- General Comment 25 of the UN Human Rights Committee interpret right to political participation more narrowly, as not requiring a particular form of government. This was affirmed by the ICJ’s Nicaragua case. GA Resolutions 45.150 and 45/151 confirm this.

- “International law does not require a specific political system and does not bind non-democratic states to democratization” (263).

- “The right to self-determination cannot be consummated through the existence of a democratic, multiparty, electoral system alone”, and in absence of adequate mechanisms for the protection of numerically inferior peoples, may even lead to its violation (266).

- “In international law as it currently stands, a multiparty democracy is neither a necessary nor sufficient condition for the realisation of the right to self-determination” (268).

Tullberg, J. and Tullberg, B.S. (1997) ‘Separation or Unity? A Model for Solving Ethnic Conflicts’

Tullberg, J. and Tullberg, B.S. (1997) ‘Separation or Unity? A Model for Solving Ethnic Conflicts’, Politics and the Life Sciences, 16 (2), 237-48.

- Ethnic separation should be regarded as an alternative to national unity, to be made democratically by the group proposing it. If approved, it should include population transfers. (237).

- “A separate culture is the raison d’etre of a separate state” (237).

- Involvement of outside powers is often decisive.

- Separation tends to recreate old problems with reversed roles: members of old majority group become new minority in secessionist state.

- New borders are required as part of a radical plan for change: aim – “to leave as few people as possible in the “wrong” state” (238): move towards homogeneity required.

- Equal number in each state;

- Natural border.

- Both states may benefit by having a unified population (239). Three principles:

- Each state is responsible to accept people of its own nationality;

- Each state entitled to evict members of the other group;

- Each individual may emigrate to the ‘right’ state. (239)

- “An examination of the alternatives reveals that nothing comes close to solving the problems in the long run.” (239).

- Fundamental incompatibilities require a civilised divorce.

- Power-sharing arrangements are difficult to achieve and incompatible with democratic principles and methods (239) based on the basic value of equal citizenship rights. Consociationalist solutions are temporary, not long-term. (240).

- Group egoism and cohesiveness to gain strength in conflict with other human groups not necessarily based on kinship ties. (241). Four categories based on human’s ‘selfish genes’ (241) – drive for genetic self-interest:

- Egoism;

- Kin selection;

- Reciprocity;

- Group egoism: product of natural selection – rational because it increases individual survival and reproduction: “it is hard to see how humans could abandon this way of functioning”; futile to even try: ethnocentric rationality (241).

- Altruism: results not from natural selection, but from cultural factors.

- Manipulation: deception by promising advantages that are not delivered. People are smart enough to eventually detect this because they are zoon politikon (241).

- How to distinguish between real group interests and deceitful claims? People’s democratically-expressed judgement should do so. (241).

- “to promote interests through ethnic alliance has been a reality in history and will continue to be so. It seems futile to try to rid humankind of ethnocentrism by declarting it outmoded or calling it a mental malady, xenophobia” (241).

- “A monolingual society has an obvious practical advantage over a multilingual society” (242).

- Outside control of resources and job competition with immigrants can be harmful to the welfare of one’s own group (242).

- “That irredentas are so seldom chosen is hard to explain for any reason other than that the leadership of the minority prefers being the ruling elite of a small entity to being integrated into a larger unity of the common creed, language, etc.” (242).

- Origins of ethnic oppositions lie on long-standing conflicts: historic animosity between neighbours outweighs difference; ‘contact-hypothesis’ not enough to remedy this.

- Nationalism is a modern variant of ethnocentrism. (243).

- “One way to compensate for low rank is to emphasize superiority versus the out-group.” (243).

- A group’s dissatisfaction capable of triggering separatism is rooted in exploitation by another group. Such inter-ethnic antagonism is composed both or real historical facts and constructed myths. (245). To avoid conflict, retaliation, violence, separation is a possible solution when there is no trust, belief and passion for a new start.

- Four types of objections:

- Time: globalisation and emergence of a single international culture. This runs against realities of fragmentation, disintegration, nationalism, new states’ creation, supranational organizations providing for security and prosperity assuring viability of smaller states.

- Sympathy: ‘pity priority rule’: support weak against strong group. This is disastrous for peace. Also, roles can easily be reversed -today’s victims can become tomorrow’s villains, whilst certain groups can play both roles.

- Authority: the real problem is central governments’ (or the UN’s) lack of authority to impose peace. Authority is not enough; solutions must also be legitimate, and in accordance with recognised and certain rules and principles.

- Jurisdiction: limit ethnic demands past a certain level and in effect outlaw secessions. This does not really address the underlying problem and requires an alternate plan. “Separatism cannot be transformed from a political choice to a matter of policing” (246).

- Even democrats do not want to apply a democratic solution if they believe democracy will not only not solve the problem, but bring about more conflict, violence, and death. Such pessimism is not justified, and solutions such as the one proposed here of ‘civilised divorce’ can be found.

Sambanis, N. and Schulhofer-Wohl, J. (2009) ‘What’s in a Line? IS Partition a Solution to Civil War?’

Sambanis, N. and Schulhofer-Wohl, J. (2009) ‘What’s in a Line? IS Partition a Solution to Civil War?’, International Security 34 (2), 82-118.

- Partition promises a clean and simple solution to war – but does it work?

- Arguments for partition:

- Ethnic identities are hardened by war;

- This makes interethnic cooperation difficult;

- It increases risk individuals will be targeted for violence because of their ethnicity;

- Separating ethnic groups in conflict reduces risk of escalating violence.

- Partitions has costs:

- Changes political boundaries;

- Forcibly relocates populations.

- Empirical evidence in favor of partition is weak.

- Chapman and Roeder (2007) (‘C&R2007’) reanalyses data generated by Sambanis (2000) to show partitions have strong pacifying effect after civil wars.

- This article will demonstrate the fragility of pro-partition empirical results: on basis of available evidence, partition does not have the pacifying effect C&R2007 claim it does.

- Necessary to pay attention to data coding issues, historical and political contexts, rigorous theory building.

- We “find that partition does not work in general and that the set of conditions under which it is likely to work is very limiting” (83).

- Kaufmann claims partition is a good solution if groups can’t live together in ethnically hetereogeneous states because it resolves the ethnic security dilemma: it reduces threats each group poses to the other.

- Partition: “a civil war outcome that results in territorial separation of a sovereign state” (84).

- “Redrawing borders, with or without substantial physical separation of people, is often unsuccessful in reducing the risk of war recurrence” (85).

- Three historical examples indicate that partition might work under certain conditions: Cyprus, Bangladesh, Croatia, Eritrea, Somaliland.

- C&R2007 develop an “institutional bargaining” model arguing that de jure partitions resulting in creation of new sovereign states reduce likelihood of escalation in hostilities in short run.

- Their results are due to methodological mistakes. Their claim that partitions should outperform all other solutions to civil wars over competing nation-state projects because “they simplify the nature of bargaining between elites of the secessionist region and elites of predecessor state, reducing opportunities for violence escalation” (87).

- Ethnic Security Dilemma (‘ESD’) set out by Posen (1993):

- Without impartial state policing, ethnic groups become responsible for own security and risk escalation because of “tactical offensive advantage” (94). Therefore, each group attempts to ethnically cleanse its territory of potentially hostile ethnic groups, leading to rapid escalation of violence in a preemptive war.

- ESD puts political geography at the centre and claims that partition removes tactical offensive advantage if near-complete physical separation of antagonist ethnic groups is achieved.

- ESD asserts that ethnic power sharing is particularly unstable, that ethnic identity is easily identifiable, and that this makes targeting of individuals for violence after an ethnic war particularly easy.

- Unstated key condition: presence of powerful coethnics in a neighbouring state is a key component of the escalation logic of the security dilemma; this implies against logic of partition “that neighboring states can both deter and catalize an escalation of violence regardless of demographics” (95).

- “Ethnic power sharing need not be inherently unstable; conflict escalation often results from external intervention and not from the country’s ethnic demography. Focus on ethnic demography assumes fixity of ethnic identities and ease of ethnic identification, which underpin position that partition is potentially useful only in ethnic wars (96).

- “The ethnic security dilemma applies only under conditions of state weakness, and the argument boils down to a credible commitment plan” (96). Partition is only one of several ways through which the credible commitment problem might be addressed” (98).

- Security dilemma does not apply only to ethnic wars, but also to those arising out of political beliefs and affiliations to any number of social groups (97). It ceases to apply to residual minorities and is exacerbated by certain demographic patterns, all of which must be taken into account when evaluating conditions under which partition might work.

- Institutionalists argue that partition is supposed to have a pacifying effect and reducing hostility by simplifying postwar bargaining between elites of a secessionist state and elites in the predecessor state (98). They opine that partition eliminates conflict by:

- Strengthening the collective identity of the secessionist region’s inhabitants and reducing the claims of the rump state to its territory and inhabitants;

- Eliminating causers of conflict by minimizing joint decisions that need to be taken jointly by the central government of the rump state and the leaders of the secessionist region;

- Raising the costs of escalating conflict by transforming it into an international one;

- Giving both sides more visible and defensive military positions, thus achieving ‘a balance of capabilities’ (99).

- These arguments rest on ad hoc assumptions that are not proven.

- Even if partition solves a conflict by separating populations that do not trust each other to cooperate in a unitary post-war state, it can generate new incentives for new identity or distributional conflicts in bot rump and secessionst states (101):

- Within new state for government control;

- With new group trying to secede from new state and join rump state;

- Within rump state over government control;

- Within rump state for distributional resources after departure of a resource-rich territory;

- Between rump state government and other minorities as result of secondary consequences of partition.

- Data shows that partitions do not have the anticipated positive and significant effect on post-war peace. (107).

- Peace transitions are nonlinear processes: one step forward – two steps back.

- “The best available evidence shows no significant association between partition and postwar stability, defined as a lower risk of a return to war” (116).

- “Ethnic cleansing, once considered a humane way to manage conflict, has fallen out of favour. In many ways, partition just takes the problem and calls it a solution” (117).

- The ‘institutional model’ offers weak foundations for arguments in favor of de jure partition as a solution to civil war (118).

- “Institutional arguments assume that contentious identities will be quickly transformed by partition, whereas security dilemma arguments assume that contentious identities cannot be transformed. Yet neither argument has dealt with the institutional effects of partition on ethnic identity properly; both assume away the problem that new identities and distributional conflicts can be created by partition” (118).

Weller, M. (2005) ‘The self-determination trap’

Weller, M. (2005) ‘The self-determination trap’, Ethnopolitics 4 (1), 3-28.

- The Classical doctrine of Self-determination (‘SD’) disenfranchises populations and does not satisfy those struggling for sovereign statehood., resulting in prolonged and bloody armed conflicts.

- The emerging doctrine of constitutional self-determination could point the way out of this deadlock.

- International system balances ideology of free will and need to maintain order, stability and peace by ensuring that the doctrine of SD is constructed in a way that limits or denies choice. However, this dynamic does not prevent conflict – it sustains it: state will label groups asking for recognition as secessionists and rebels, whilst opposition movements will radicalize their demands and see armed struggle as only way forward.

- Virtually all opposed unilateral secessions resulted in violent conflict and were either defeated in a violent conflict or festered for decades.

- In recent years, central governments, SD movements and international actors have tried to escape the SD trap by devising new settlements attempting to reconcile SD and territorial unity through complex power-sharing agreements such as constitutional self-determination (‘CSD’).

- SD disenfranchises populations by proceeding in 5 steps:

- SD is linked with the doctrine of territorial unity;

- SD limits the type of ‘people’ entitled to exercise this right;

- SD scope of application is very narrow;

- SD is not a continuous process, but a one-time event;

- Modalities of achieving the point of SD.

- SD: right of all peoples to freely determine their political, economic and social status both internally (choice of system of governance) and externally (secession). It has various sub-meanings:

- SD as an individual right;

- SD as congruent with minority rights (individuals or groups);

- SD for indigenous peoples;

- SD in cases of limited territorial change;

- External SD.

- Focus here will be on SD as entitlement of ‘peoples’ to determine the international legal status of a territory.

- International law protects claims of existing states’ governments to their territories and will only grant Secession demands if the government concerned consents. There are three instances when this can happen:

- When one state joins another (GDR joining FRG);

- Dissolution of composite states (Czechoslovakia, USSR);

- Instances of secession (Eritrea).

- Manifestation of popular will is necessary even when the central government agrees to secession.

- Traditional SD right asserts its validity irrespective of the wishes of the central government – ie. right to unilateral and mostly opposed secession.

- First element of disenfranchisement:

- States have enshrined doctrine of territorial unity in international law and connected SD only with an exceptional right to secession, only available in cases of decolonization of state consent. All other Secessions are considered unlawful – thus effectively disenfranchising populations that want to exercise SD.

- Second element of disenfranchisement:

- Opposed unilateral secessions that do not involve the unlawful use of external force, genocide, apartheid, etc. are not internationally unlawful (9).

- An entity that secedes and effectively maintains itself over time can eventually obtain statehood and extinguish the claims of the original state over its territory. But this is difficult to determine, and original states can always attempt to reincorporate break-away entities.

- SD entities are internationally privileged before they obtain their effective independence in a way ‘effective entities’ are not: the latter must fight forcible reincorporation and win decisively over time to mature into recognized states.

- Third element of disenfranchisement:

- Colonial SD has been recognized only for a limited category of entities (overseas colonies in the global South, alien occupation – Palestine -, racist regimes -South Africa, secondary colonies – East Timor – , and does not extend to territorially contiguous imperial states (Chechnya, Kosovo).

- “While self-determination is an activist right that is intended to overcome the evils of colonialism, it is in fact administered in a wat that is consistent with the territorial designs and administrative practices imposed by colonizers” (11).

- The ‘people’ entitled to SD are those living within colonial boundaries drawn by colonial powers.

- Aim of decolonization is not restoration of situation before colonialism, but reshaping of facts based on reality of colonial administration. It is the territorial shape of that administration that defines the SD entity, not the will of the people.

- African states accepted these colonial boundaries upon independence and “fiercely defended them” in the name of stability and order (12).

- Badinter Commission endorsed this doctrine of uti possidetis as a universal principle across the world.

- Fourth element of disenfranchisement:

- Colonial SD occurs only once – not an on-going process.

- Subunits have to similar SD rights (Badinter Commission).

- Fifth element of disenfranchisement:

- Imbalance in status of those struggling for independence outside the colonial context;

- Those within colonial context but which are subunits of colonial administrative entities achieving independence;

- Entities that oppose initial SD act integrating them with another entity and seeks independence.

- Entities that qualify under classical SD are legally entitled to struggle for independence and receive international assistance; those who do not, cannot.

- In cases within colonial context, the system ensures the liberation struggle will be a success; outside it, “the system is rigged in order to ensure that the state prevails” (14): the struggle is classified as a purely internal domestic rebellion and rebels can be treated as criminals.

- Double disenfranchisement: domestic and international.

- Two recent exceptions:

- Stalemate no longer acceptable domestically (Northern Ireland);

- Humanitarian suffering results in external armed intervention (Bosnia).

- Emergence of doctrine of constitutional SD.

- Colonial SD is based in international law; Constitutional SD is based on a constitutional arrangement establishing separate legal personality for component parts of an overall state.

- Four types of Constitutional SD:

- Express SD status: specified in a state’s constitution (Ethiopia): very restrictive;

- Effective dissolution of a federal-type state (USSR; Yugoslavia): with conditions attached:

- SD right constitutionally specified;

- Only constituent federal republics possessed SD rights (excludes Kosovo, Chechnya);

- Free and fair referendum;

- Acceptance of minority rights guarantees.

- Implied SD status:

- when a ‘nation’ or ‘people’ inhabit a constitutionally defined territory and the central government or constitution grant SD referendum rights (Scotland, Quebec)

- Independence not automatic: both parties must engage in ‘good faith’ negotiations about implementation of decision to secede.

- SD though adverse conduct by central authorities:

- Badinter Commission: federal-type entities denied effective representation in political structure of federation;

- Entity suffered genocide or ethnic cleansing or deliberate campaign to destroy its population.

- Effective entities: No SD status, but de facto statehood: untested theory.

- SD through Internationalized Settlements: self-government of secessionist units coupled with power-sharing mechanisms in the larger state, under international supervision, allows escape from SD trap (Northern Ireland, Bougainville)

- “The existence of the right to self-determination therefore served as a convenient legitimizing myth for the existing state system” (26).

- “The state was given a carte blanche in dealing with groups seeking to assert their separate identity” (26-7).

- SD is mostly a hollow promise – even a curse: the system is rigged in favor of central governments: by privileging stability over ‘justice’ it sacrifices peace (27).

- Settlements are being achieved in instances of mutually harmful stalemates through various power-sharing arrangements or long-term possibilities of separation: necessary to escape the current SD trap though new forms of co-governance or eventual secession.

Sambanis, N. (2000) ‘Partition as a Solution to Ethnic War: An Empirical Critique of the Theoretical Literature’

Sambanis, N. (2000) ‘Partition as a Solution to Ethnic War: An Empirical Critique of the Theoretical Literature’, World Politics 52 (4), 437-483

- Partition theorists have not produced operational criteria for applying their theories consistently across cases.